The concept of inequality and the political practice of imperialism employed by the Romans during their 400-year rule left a lasting impact even after the fall of the Roman Empire.

The concept of inequality and the political practice of imperialism employed by the Romans during their 400-year rule left a lasting impact even after the fall of the Roman Empire.

The historian Julia Smith, who studies the history of the early European Middle Ages, gives a detailed account of the impact of Roman imperial culture on the population of Europe after 500 AD. She describes the early medieval period of European civilization that by the 5th century had developed from the western Roman imperial provinces into independent, separate kingdoms in which regional diversity and locality were coupled with many aspects of the Roman cultural, religious and political heritage. The concept of inequality, which had led to the development and to the legitimation of imperialism, influenced people’s lives at that time on many levels, which also included gender relations. Smith refers to the adoption of Roman law, which favored adult men over minors and women by granting them broader rights in disputes and promoting a patriarchal hierarchical structure. This involved drawing on an imaginary and mythical past to legitimise privileged local, political and economic positions and limitations on authority that ensured the transfer of power among the male ruling elite. According to Smith, Christianity was instrumental in the transmission of Roman culture, which was then preserved by the churches. The concept of imperialism was enforced through the Latin Bible and its references to many ancient empires, of which Rome was portrayed as the youngest. The term “empire” was widely used in early medieval Europe to describe various forms of military, political, and cultural rule, and imperial practices were used to demonstrate power and enhance its legitimacy.

Smith describes a fundamental change that began in the 11th century and continued into the 13th century, triggered by the establishment of a papal monarchy that began to exercise centralized judicial and administrative authority over Latin Christianity. According to Smith, this centralization destroyed all forms of local diversity that had existed until then. Smith describes how the former cultural hegemony of the Roman way of life was now replaced by Christianity, which had by then incorporated many of the Roman cultural elements. The church needed land, capital, treasure, and ideological support to maintain its dominant position. According to Smith, the hegemony of the church in medieval Europe influenced the social structure of European societies at many levels and promoted inequality in gender relations, social status, and political and economic power relations (Smith, 2005).

Smith describes a fundamental change that began in the 11th century and continued into the 13th century, triggered by the establishment of a papal monarchy that began to exercise centralized judicial and administrative authority over Latin Christianity. According to Smith, this centralization destroyed all forms of local diversity that had existed until then. Smith describes how the former cultural hegemony of the Roman way of life was now replaced by Christianity, which had by then incorporated many of the Roman cultural elements. The church needed land, capital, treasure, and ideological support to maintain its dominant position. According to Smith, the hegemony of the church in medieval Europe influenced the social structure of European societies at many levels and promoted inequality in gender relations, social status, and political and economic power relations (Smith, 2005).

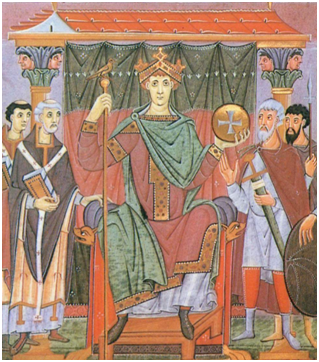

On a political level, it is important to mention that after the fall of the Roman Empire, Charlemagne expanded the Frankish Empire into a major European power from 768 to 814 by conquering surrounding tribes. He himself supported and promoted Christianity and was crowned emperor by Pope Leo III in the year 800 and was thus able to portray himself as the successor to the ancient Roman Empire. After Charles’s death and his son Louis’s assumption of power, the empire was divided among his sons, which led to the creation of the West and East Frankish Empires (later France and Germany). Otto I, a descendant of Louis, who was crowned Emperor of the East Frankish Empire in 962, took up the idea of the renewed Roman Empire and the name Holy Roman Empire can be found documented since 1184.

The historian Brendan Simms describes the 13th century Holy Roman Empire, which stretched from Brabant and Holland in the west to Silesia in the east, from Holstein in the north to just below Siena in the south and Trieste in the southeast and was at the center of European power disputes. The empire was led by an emperor who was elected by eleven voters. He ruled in consultation with the lay and ecclesiastical “estates” of the empire, as well as the voters, princes, knights and cities gathered at the Reichstag (Simms, 2014)

In the following blogs we will focus on the subsequent social crises in early European and German history.

Bibliography

Simms, B. (1998). The Struggle for Mastery in Germany 1779-1850. London: Macmillan Press.

Smith, J. (2005). Europe after Rome. Oxford: Oxford UP.

Images

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frühmittelalter

https://www.leben-im-mittelalter.net/geschichte-des-mittelalters/fruehmittelalter/christianisierung.html