Die Schlacht am Weissen Berg, 1620

Die Schlacht am Weissen Berg, 1620

Socio-political background

The split in the religious unity of Europe initiated by Luther in 1517 led to a local uprising of Bohemian Calvinists against the Catholic Habsburgs in 1618, which turned into a European war with religious and imperial motivations. Reinhardt describes how rivaling principalities of different denominations called for foreign support in their campaign against each other, leading to a war in Europe in which Spain-Austria and France-Sweden were the main opponents. The intervention of foreign powers significantly prolonged the conflict. When the war ended in 1648, the German principalities had lost their sovereignty as well as a significant number of territories, including Alsace-Lorraine, to France. According to Reinhardt, the Thirty Years’ War was a struggle for power and supremacy in Europe, fought under the banner of religion, and with far-reaching consequences for later political conflicts. In this context, Reinhardt describes the imperialist efforts of the Swedish King Gustav Adolf, the German General von Wallenstein and the French Prime Minister Cardinal Richelieu (Reinhardt, 1950).

The extent of the hardship experienced by the population in many areas is evident in the following writing from a village cobbler’s diary from 1634:

‘Duke Bernhard’s troops broke into our land and plundered us completely of horses, cattle, bread, flour, salt, lard, cloth linen, clothes and everything we possessed. They maltreated the people, shooting, stabbing and beating a

number of people to death… while we were holding out at the church, they set alight the village and burnt down five stables…. Because the troops were in pursuit of their enemies they laid waste to everything, plundering the little town of Giengen and burnt it down. The town of Geisslingen in Ulm territory weakly tried to defend itself. It was overrun and several hundred people were massacred. The pastor had his head cut off, and the place was devastated… Everyone had to flee to the city once more and we stayed the whole winter there. It was real hardship, famine and death. We were crowded together and lived in great want. Hunger and price increase came at the same time. And after that the evil disease, the pest. Many hundred people died of it in this year and also in the next’

(Benecke 1978: 31, 33)

Überfall auf einen Bauernhof Jaques Callot, 1633

Überfall auf einen Bauernhof Jaques Callot, 1633

An English contemporary describes the situation as follows:

‘Germany… is now become a Golgotha, a place of dead men’s skulls and the Aceldama, a field of blood. Some nations are chastised with the sword, others with famine, others with the man-destroying plague. But poor Germany hath been sorely whipped with all three iron whips at the same time and that for over twenty years’

Edmund Calamy 1641

Socio-cultural Background

The historian Gerhardt Benecke describes the great importance of the Christian religion at this time, which applied to all areas of life, and the influence of the pastor and his weekly sermons. He makes clear that religious indoctrination led the population to view crises and challenging experiences as punishments and as a sign that their sins had incurred the wrath of God (Benecke, 1978). Since a general perspective on life had developed since the Middle Ages that valued the afterlife higher than current life experiences, experiences of crisis were hardly recognized as such and therefore rarely expressed through cultural productions.

The German literary scholar William. A. Coupe describes how events that seemed inconsistent were commented on through politically satirical pamphlets. This form of satire developed during the Thirty Years’ War as a variation of the religious satirical pamphlets that emerged during the Reformation. The political satirical pamphlets, published at irregular intervals, expressed emotional tensions and, through the satirical element, facilitated the confrontation of the ideal with the real (Coupe, 1962). The picaresque novel contains a similar satirical element, of which Simplicius Simplicissimus von Grimmelshausen (1668) is the best-known example. The novel is set during the Thirty Years’ War, contains autobiographical elements and gives a narrative account of the war years, written in the first-person singular. This creates an apocalyptic atmosphere in which the world is portrayed as a madhouse and violence as a daily, unpredictable experience.

While war is illustrated in all its violence, the main intention of the novel is to educate its readers morally. Another cultural example that expresses the experience of the social crisis at the time is the lullaby “Horch Kind horch…”. The song refers directly to the experience of the Thirty Years’ War and conveys the atmosphere of fear and uncertainty that characterized this time.

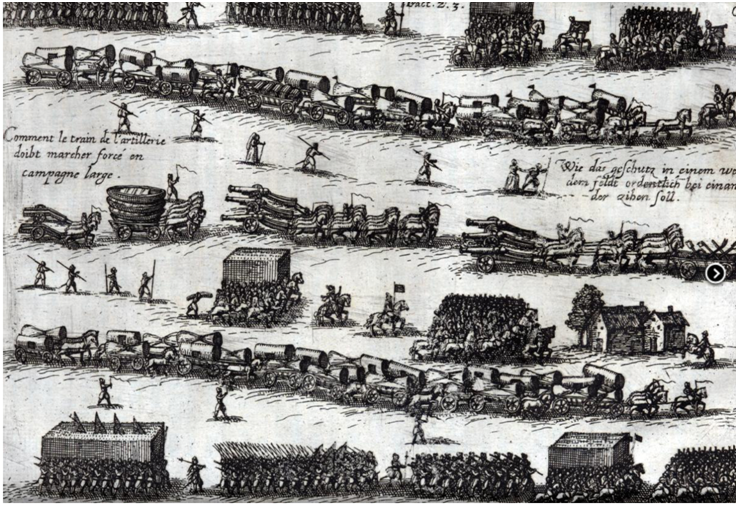

Waffengattungen, Diego Ufano Archeley, Frankfurt 1614

Waffengattungen, Diego Ufano Archeley, Frankfurt 1614

The cultural sample the lullaby Horch Kind horch wie der Sturmwind weht

Listen, child, listen as the storm wind blows and shakes the bay window

When the Braunschweiger stands outside, he grabs us even more

Learn to pray, child, and fold your hands piously

so that God can turn the mad Christian away from us

Sleep child sleep, it’s bedtime, it’s also time to die

If you are big, the drum will recruit you far and wide

Run after her, my child, listen to your mother’s advice

If you fall in battle, no soldier will choke you

“Soldier, don’t hurt me and leave me my life!”

“Duke Christian leads us to a fight and can give us no quarter

The farmer has to leave me his goods and belongings

don’t pay with money, just with the cool grave”

Sleep, child, sleep, grow strong and grow up as the years roll by

Soon follow Duke Christian the Mad yourself on your proud steed

How frightened the priest is and throws himself on his knees

“No pardon for the farmer, but never for the priest!”

Quiet, child, quiet, when Mr. Christian comes, he teaches you to be silent!

Be quiet until you feel like getting on your horse

Be quiet and your father will soon bring you bread

If the wind doesn’t taste like smoke and the sky doesn’t taste red

Interpretation of the song lyrics

The lullaby contains 5 stanzas with 4 verses each. Each verse, apart from the third, middle verse, contains elements typical of a lullaby. A mother speaks to a toddler, the child is told to sleep, calm down, grow up and be strong, pray and be pious. Some of these prompts contain repetitions such as: Listen child listen, sleep child sleep and hush child hush. In the lyrics of the song, the mother refers to the child’s immediate surroundings: to the stormy wind shaking the house; to the evening, the time to sleep; to the years that pass. These references are linked by associations that stand connection to the daily experience of war: the wind that shakes the house is like the intruder that violently seizes the family; the time to sleep is also the time to die; the years that pass bring the child closer to his own participation in the war. Stanza 3 contains a dialogue between a victim of violence and a perpetrator, illustrating the lack of mercy and social justice of the time. The way he is addressed makes it clear that the victim is a peasant and that the perpetrator is a soldier. While the victim only speaks in one verse pleading for his survival, which illustrates his helplessness, the perpetrator explains in three verses that mercy is not part of his mission and that the farmer must give him everything he has, for which he will then be murdered in return.

The basic model of Greimas’ story can also be found in the text of this lullaby. While the child can be seen as a ‘subject’, the ‘object of desire’ is his own safety, the ‘adversary’ is the warmongering Duke Christian and his soldiers, the ‘helper’ is the mother and the ‘super-helper’ is God. The lullaby itself can be seen as part of the mother’s attempt to help, warning the child of the cruel reality that awaits him and trying to protect him from the worst.

According to Toolan’s method of narrative analysis, character traits can be revealed through actions when they are not described by adjectives. The characters mentioned in the song are:

1.the child to whom the song is sung and who can be identified as a male child by his expected action of riding a horse and joining the army

- the mother, who identifies herself as an advisor in the third person singular in the third line of the second stanza

- the father, who is described towards the end of the song as the bringer of bread and thus as the one who provides the child with the daily necessities

- God who can protect the child from harm

- Duke Christian, described as wild and unpredictable by the adjective ‘mad’, as well as proud and powerful by his elevated position on horseback, while his actions characterize him as merciless and cruel.

It is the Duke’s warmongering nature that has created two conflicting groups, the farmers and the clergy as victims and the Duke’s soldiers as the perpetrators. Peasants and clergy are depicted as humiliated and helpless through their pleading and kneeling in shock and fear, the soldiers as proud and powerful on the backs of their horses. The cruel attitude of the Duke and his soldiers is evident in their speech and sarcasm: the peasant’s payment for his goods is his cooling grave and there is no mercy for the peasants and never mercy for the clergy.

The fear expressed in the second line of the first stanza that an intruder might seize the family gives a hint that the group to which the child belongs could easily be among the victims. In this situation of violent oppression, where only victims and perpetrators exist, the choice is between death as a soldier in battle or being murdered by a soldier at home. The mother’s advice to the child is to join the army. While it becomes clear that security as the ‘object of desire’ cannot be achieved, the humiliation of being robbed and murdered at home is seen as worse than death in battle. “If you fall in battle, no soldier will choke you.” The lullaby begins with a reference to the stormy wind shaking the house, describing the forces of nature as powerful and as violent as the enemy. In the last line, even the forces of nature seem to be affected by war. The wind tastes like smoke and the sky is red. This close connection between war and nature, both described in their raw, untamed and threatening state, creates an atmosphere of doom and conveys an overwhelming impression of helplessness.

Conclusion

The lullaby ‘Horch Kind horch…’ is one of the few cultural productions that express the life experiences of the Thirty Years’ War. However, it must be pointed out that these experiences were not shared equally by all German-speaking principalities and that the song refers specifically to the experience of the people in the Lower Saxony district.

The imperial motivations underlying the Thirty Years’ War illustrate the connection to the Greco-Roman legacy and the concept of inequality that enabled the legitimization of violence. The extent of the hardship that the population of the affected principalities had to endure can be seen in the portrayals of their contemporaries and in the extent of the fatalism of the cultural productions that referred to the war experience. Due to religious indoctrination that attributed responsibility for every hardship to the individual’s sin and a perspective that focused on the afterlife rather than the present, the number of cultural productions that depicted the experiences of war and acknowledged the violence encountered was significantly reduced. The few productions that attempted to address these experiences had their own limitations and were restricted in their reception: political satire only referred to experiences of incongruence, the novel Simplicius Simplicissimus was limited by its didactic intentions and only accessible to the few that could read and write at that time and the lullaby ‘Horch child horch’ only refers to a specific region. Coupe points to the far-reaching implications of this inability to express social crises culturally by pointing out that in countries such as England and Holland, the medieval iconographic tradition from which religious and political satire had developed continued to evolve into the medium of caricature developed while satirical production in Germany stopped after the Thirty Years’ War. Coupe attributes this development to the “absence of a healthy political life or of an active and vocal political opinion in Germany for a century and a half” (Coupe, 1962). This absence can be understood as a collective response to the experience of the Thirty Years’ War, which bears similarities to the dissociative response to traumatic experiences at the level of individual psychology. In a social context, Scheff (2007: 8) observes two possible responses to unacknowledged experiences of loss, anger and shame:

1) Withdrawal and silence.

2) Anger, aggression and violence.

Since the religious perspective of the time encouraged focus on the afterlife and thus withdrawal from current reality, the choice of a collective response of silence and dissociation is easily explained. The lack of collective identity that arose from the experience of violence and social injustice among the population of the German principalities will remain relevant for the following blogs.

Bibliography

Benecke, G. (1978). Germany in the Thirty Years War. London: Edward Arnold.

Coupe, W. A. (1962). ‘ Political and Religious Catoons of the Thirty Years War. Journal of the Warburg and the Courtaud Institutes, 1/2(25), 65-86.

Reinhardt, K. F. (1950). Germany: 2000 Years. California: The Bruce Publishing Company.

Scheff, T. (2007). War and Emotions: Hypermasculine Violence as a Social System. Retrieved March 8, 2009, from http://www.soc.ucsb.edu/faculty/scheff

Toolan, M. J. (1988). Narrative: A critical Linguistic Introduction. London : Routledge.

Images

Die Schlacht am Weissen Berg 1620, Interfoto

Überfall auf einen Bauernhof Jaques Callot, Museum Dreißigjähriger Krieg, Wittstock

http://www.mdk-wittstock.de/seite/9046/museum-dreißigjähriger-krieg.html

Waffengattungen, Diego Ufano Archeley, Frankfurt 1614, Museum Dreißigjähriger Krieg, Wittstock

http://www.mdk-wittstock.de/seite/9046/museum-dreißigjähriger-krieg.html