Still from the film Das Vermächtnis

Still from the film Das Vermächtnis

Socio-political background

According to Pulzer, the rapid growth of the German economy, the empire’s competition with other European states for colonies, the development of an aggressive program of military expansion, and a series of diplomatic crises had led to a tense international atmosphere in 1914. When Germany became involved in a war between Austria, Hungary, and Russia, the initially regional conflict escalated into a world war due to a complicated system of alliances. Pulzer describes how the war was seen by many as an opportunity to realize their dreams and expectations. This enthusiasm in Germany was also based on the understanding that it was a defensive war that would quickly lead to victory (Pulzer 1997). Historian Hans Maier explains how the reality of World War I was far from this vision, as it was, due to the rapid development of technology and transport, an industrialized and total war that affected not only the armies but also the entire population and lasted four years (Maier, 2001). According to Reinhardt, German casualties amounted to 1,600,000 dead, over 4 million wounded, and over 200,000 missing. Another 250,000 deaths were due to malnutrition in the immediate aftermath of the war (Reinhardt, 1950). Pulzer describes the humiliation and collective outrage that followed when the peace treaty was published. This included substantial reparations, the loss of all colonies and territories such as Alsace-Lorraine, the reduction of the German army to 100,000 men, the occupation of the Rhineland by Allied troops for 15 years, the surrender of the German battle fleet, and the prohibition of the Austrian Republic from joining the Reich against the will of its people. The end of the war had also been a time of intense social unrest, which included revolutionary uprisings. When the German fleet was ordered to regain its honour in one final battle, a mutiny broke out in Kiel, spreading from the marines to the shipyard workers to the trade union representatives, sending the spirit of revolution to every major city with the intention of establishing a socialist republic.

Aufmarsch des Rotfrontkämpferbundes still from the archive material

Aufmarsch des Rotfrontkämpferbundes still from the archive material

Pulzer explains that President Wilson insisted on the democratization of Germany as a prerequisite for peace negotiations. Public order therefore had to be restored at all costs. To this end, a secret alliance was made with the army and when another revolution broke out in Berlin in January 1919, it was crushed by the regular officers, who captured and murdered the leaders of the revolution, Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg. A communist government in Munich, established in February 1919, was also ended by the army in a massacre lasting several days. Pulzer reports how the experience of war and the German defeat, with its political, economic and social consequences, led to a significant increase in tensions, social unrest and violent tendencies, which increased with the rise of inflation (Pulzer, 1997). Mosse describes how the ‘völkische ideology’ that had developed among the German middle class during the course of the 19th century gained importance after the end of World War I and the establishment of the Weimar Republic. This distorted view began to spread throughout all parts of society and gained a political base supported by majorities (Mosse 1964).

Socio-cultural background

Socio-cultural background

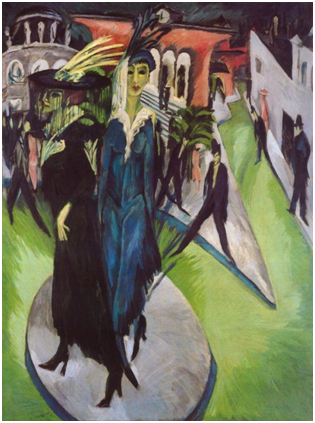

While artistic conventions initiated and institutionalized by the German bourgeoisie had become established in the 19th century to promote a sense of national identity, alternative counter movements in art soon developed. Expressionism was one of these movements and encompassed all cultural media such as literature, fine arts, theatre, music, dance, film, etc. (Lehman, 1997). Cultural critic Douglas Kellner sees Expressionism as one part of a series of anti-capitalist avant-garde revolts in Europe in the early 20th century. According to Kellner, the Expressionists promoted a focus that was on subjective experience and the pursuit of social transformation while attempting to attack the established norms, values, institutions, and established artistic conventions. Kellner emphasizes that Expressionism was most influential in Germany because industrialization and the spread of capitalism were particularly rapid and uneven, resulting in a social atmosphere marked by tension. Kellner describes how Expressionists critically confronted modernity, demonstrating the impact of new modes of transport and urban life, and incorporated developing mass media such as film to reflect the pace and multi-layered complexity of the modern life experience. While the middle classes established the narrative of the idealized nation and its mythical past, the Expressionists deconstructed this idea in order to face the crises of industrial reality, challenging the established norms of bourgeois society with its conservative, militaristic and nationalistic tendencies (Kellner 1983).

Kriegskrüppel, Otto Dix, 1920

Kriegskrüppel, Otto Dix, 1920

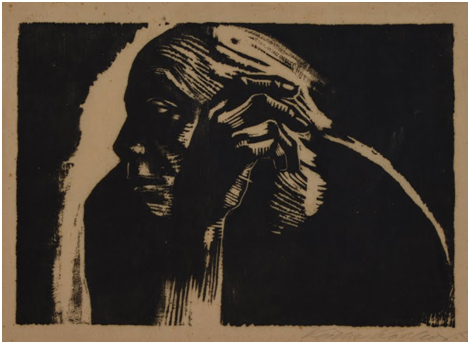

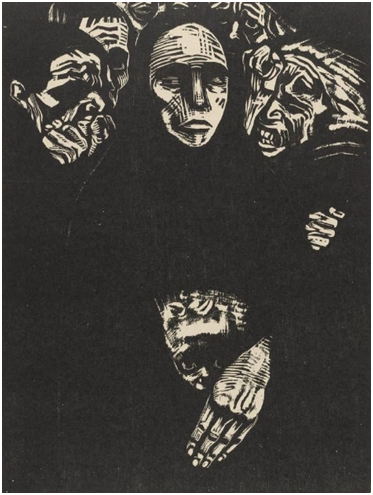

The cultural example Das Volk, a woodcut by Käthe Kollwitz that dealt with the experience of the First World War, can be attributed to early Expressionism. Art historian Elizabeth Prelinger explains that the influence of the Expressionist movement in Kollwitz’s work is limited to the war cycle and political posters, where it is the intensity of the emotional content that links this part of her work to early Expressionism. Kollwitz’s commitment to social and political issues was also a concern she shared with the second generation of Expressionists.

Käthe Kollwitz was able to escape the rigidity of the Prussian public school system. She was privately educated and influenced by an unconventional family background marked by both religious and socialist sentiments. Deciding to become an artist at an early age, Kollwitz was quickly attracted to the social reality of the working class and believed in an art that had a social calling. Due to the political controversies of her time, she was considered a socialist despite her outspoken apolitical position. The woodcut Das Volk (the people) is part of a war cycle completed in February 1921 and published in 1924. Kollwitz addressed the subject from her personal perspective after her youngest son, Peter, was killed at the front in 1914. While Kollwitz had initially shared her son’s enthusiasm for volunteering, her attitude toward the war changed with this experience to the outspoken and committed opposition evident in the cycle. Inspired by the work of sculptor Ernst Barlach, Kollwitz turned to woodcut as the medium for this series, adopting a number of expressionist effects such as simplification and distortion to enable direct communication with the viewer.

What distinguished Kollwitz from other expressionist artists was her affinity with the naturalistic tradition from which she emerged and the fact that she was integrated into the establishment as a member of the Secession and a professor at the Prussian Academy of Fine Arts. Prelinger highlights that most

Self-portrait , Kaethe Kollwitz, Holzschnitt 1924

Self-portrait , Kaethe Kollwitz, Holzschnitt 1924

avant-garde artists had lost touch with the general population, while one of Kollwitz’s main concerns was to be accessible to everyone. Kollwitz was different from other expressionist artists in that she was fully integrated into her social environment, and she was accepted by the public because her work fit well within the kind of socially oriented imagery that had been promoted by artists of the previous generation such as Menzel and Liebermann. While she pursued her own figurative style, her engagement with socially inspired themes was due both to her upbringing and to her later life experiences as the wife of a working-class doctor in Berlin (Prelinger, 1992). Like her contemporaries, Kollwitz was not only sensitive to the tensions of her time but also often felt emotionally affected by what she called ‘political misery’. She speaks of gloomy moods and depression in her diaries, recognizes similar problems in her colleagues, and describes a social and political atmosphere that was increasingly oppressive and disturbing (Frank, 1982).

The woodcut Das Volk is one of the few German cultural productions to deal with the experience of World War I. Other works that directly relate to the war include Rainer Maria Remarque’s autobiographical account All Quiet on the Western Front (1929) and the works of expressionist painters such as George Grosz, Otto Dix and Max Beckmann, who chose a satirical perspective in their work. Expressionist films indirectly reflected the war experience such as Der kranke Tod by Fritz Lang (1921), which focuses on the experience of loss, grief and fate; Der letzte Mann von Murnau (1924), which deals with the feeling of shame and loss of social status; and Hamlet by Gade und Schall (1921), which expresses the experience of disillusionment with civilization and progress.

Analysis of the Woodcut Das Volk by Käthe Kollwitz

The woodcut Das Volk is part of a series of woodcuts by Käthe Kollwitz entitled Krieg (War). The application of narrative analysis to the woodcut is limited because cultural productions in the visual arts are not time-based. However, because the woodcut captures a moment in time and thus has a certain narrative character, the methodology applied to earlier cultural examples can also be used here to a limited extent.

The theme of the woodcut’s narrative is made clear by the title: Das Volk (The People). As part of the War cycle, it is implied that war is also part of the narrative and indirectly appears in the depiction through its effect on the ‘people’. According to Ricoeur, narrative texts deal with the temporal character of human experience and describe a change in the situation. The effect of war on the ‘people’ can be seen as this change. We do not know what the situation of the ‘people’ was like before this impact, but the reaction of the ‘people’ depicted suggests that this is a change for the worse. According to Toolan, character traits can be derived from adjectives or from actions, so that characters can be identified as either ‘victims’ or ‘perpetrators’.

In this case, the character of the individuals who make up the collective of the people in the woodcut’s depiction are described in their reaction to the experience of war, which is shown in their attitude and the expression on their faces. We can identify 7 people in the woodcut, 6 of whom are adults. One of the adults dressed in black, a woman in a cloak, is in the centre of the image. In the lower half of the image is a child partially covered by her cloak. The other adults, who can be partially identified as men, surround the central figure, their faces crowding into the upper part of the image. The emotions of these other adults, portrayed through facial expression and body language, range from pain and anguish to fear and worry, showing the effect of an extreme and destructive experience. Since they are portrayed in their reaction to an experience, in this case the life-threatening and destructive actions of war, they can be clearly identified as ‘victims’. The child, alone in the lower half of the picture and partially covered by the woman’s cloak, appears frightened and vulnerable and can be seen as a ‘potential victim’. The cloaked figure, who appears to be the child’s mother, contrasts with the other adult figures. To protect the child, she faces the destructive experience in the more active posture of defensive opposition and cannot be seen as a direct ‘victim’. Her upright body, stiff hand and mask-like face with an expression hardened in defiance contrast with the other adults whose faces, hands and posture are contorted in agony. To express the emotional chaos of these figures, the wood has been cut in such a way that the white cut lines of the surface appear as curves and zigzags that are multidirectional and appear disjointed and distorted. Waves and zigzags in the corners of the background continue this movement. The figure in the centre, on the other hand, is characterised by straight, slightly curved and mostly symmetrical lines on the face and hands, which are clearly ordered and give her a determined appearance as she stands in the midst of emotional turmoil. The child figure stands out due to the round shape of her eyes and the curved, regular lines of her curly hair, as well as her small nose. The child therefore appears innocent and evokes an emotional response in the viewer. The collective of ‘people’ depicted here is divided into three groups according to their different reactions to the experience of war, expressed by the quality, orientation and composition of the cutting lines. In this context, the mostly male adults at the top of the picture seem to be among those who are directly affected by the war and suffer from pain, fear and torment, the woman in the centre, as indirectly affected, defensive and protective, the child as still innocent and unharmed, but in danger of becoming a ‘victim’. This impression of a division into 3 groups is further reinforced by the positioning of the people within the picture. The men are in the background in the upper half of the picture and some are only partially visible, giving a sense of lack of space that feels oppressive. The woman with the cloak is in the centre, filling the frame. The child is in the foreground and is surrounded by the mother’s hand and her cloak, both of which come from the centre to the foreground to surround the child. The background, middle ground and foreground can be interpreted to represent the temporal sequence with which the war affects the collective, an effect that divides the group into gender and age groups. Through a force that seems to emerge from behind the picture, the men are affected first and directly, the women later and indirectly, and the younger generation last.

The hard and determined expression on the cloaked woman’s face, her central, upright and defensive position in the image, the large black surface of her black cloak, interrupted only by the partially visible face of the child, make her figure the focal point of the woodcut. It is an astonishing apparition that seems to carry a message. As the work of an artist who herself lost a son in the war, it can be read as a personal message from Kollwitz, using the cloaked woman as an example to call for a stance of active opposition in the face of war that can protect what is most valuable to the collective: the next generation. The way the image is framed, cutting off some of the faces in the upper half, suggests that only a small segment of a much larger image is visible, extending both to either side and upwards, thus hinting at the large scope of the collective of the ‘people’. As with other expressionist woodcuts, the depiction is greatly reduced. This simplification, which omits personal details that could lead to individual identification and any reference to place or time, gives the woodcut an iconic character. It thereby represents an experience that is general and can be read and understood by many because of its simplicity. Through the strong black and white contrast, the reduction of means and the intensity of the content being expressed, the viewer is addressed in a way that is both emotional and direct.

Other parts of the War Cycle are The Parents, The Widow (1 + 2), The Mothers, The Victim and The Volunteers.

Conclusion

Kollwitz chose the form of expressionism and a non-specific and simplified figurative representation to enable all members of the population to engage with the woodcut and recognize themselves in it. The chosen means enabled the direct communication of the highly charged emotional content, which expresses the feelings of fear, loss, injury and pain and calls for a stand against the possibility of another war to avoid further suffering and to protect the coming generation. While the woodcut had the potential to reach a wide audience with its message and emotional expression, it does not seem to have had the expected effect. There is one main and at least five other reasons for this.

- The representation of war that Kollwitz hoped to establish contradicted Nazi propaganda. This propaganda used the experience of the First World War, in particular the feelings of shame and humiliation that had arisen as a result of the defeat and the conditions of the Treaty of Versailles, to mobilize the population for a war of retaliation. Kollwitz made her claim from her own personal perspective as a woman addressing a female audience, calling for a spirit of resistance through the cloaked woman at the centre of her woodcut. For a female audience, the human suffering and potential loss of the children depicted in the woodcut would have had strong connotations. From the perspective of the male population, however, it was the experience of shame and humiliation that was experienced as traumatic, as these experiences questioned their identity and role in society. The loss of personal and social self-esteem was valued more highly than the potential loss of life and the suffering that came with it. The war propaganda of the Nazis, which appealed to these emotional needs and promised a revision of the loss of identity through a retaliation and victory, was able to offer the male population of the time the possibility of re-identification and emotional catharsis, successfully claiming that the defeat, not the war itself, was the trauma.

- The attitude of active female resistance demanded by the woodcut clashed with the image of the passive and submissive woman promoted at the time by the sociopolitical climate in which the tendency towards ‘hypergendering’ (Scheff 2007) was increasing.

- Nazi war propaganda was far more widely disseminated through the use of mass media and was represented by a diverse and constant presence in public spaces.

- The reception of Kollwitz’s art was also limited by the fact that she was viewed as a socialist artist.

- In a climate of fierce sociopolitical controversy and dispute, cultural media had limited opportunities to attract attention.

- The increase in censorship ultimately prevented successful communication through the woodcuts.

As already mentioned in the previous chapters, the sense of identity of the middle-class German men had been affected by the sudden industrialization, which became an experience of alienation for many and left social classes that were ideologically and socially destabilized. That this feeling of alienation was close to an experience of shame and already brought with it the potential for violence is shown by a quote from Karl Marx, who stated in a letter to Ruge in 1843 with regard to German nationalism:

“Shame is a kind of anger that is turned inward. And if an entire nation were to experience shame, it would be like a lion preparing to pounce.”

(Marx 1843 in Scheff 2007: 2).

Mosse describes how the defeat of World War I further undermined the nation’s reputation and how this loss of prestige furthered the collective experience of shame (Mosse, 1964). The fact that Nazi propaganda calling for war to restore the lost honor appealed to many, confirms Scheff’s theory that unresolved experiences of shame and humiliation are the hidden component of anger and aggression and foster antagonism toward outsiders and marginalized groups (Scheff, 2006). This tendency appeared in the form of racism and anti-Semitism, which, according to Mosse, had already been integrated into the ‘völkische ideology’ by this point. Mosse explains that the war represented a crucial period in the history of ‘völkisch’ thought, through which this ideology, which was already widespread before the war, suddenly transformed into a politically effective system of thought that gained a mass base (Mosse, 1964). Kollwitz’s attempt to establish a warning about war in opposition to Nazi war propaganda could not be effective because it did not address the experience of shame and humiliation that had affected the sense of identity of German men more than the war-related losses and the physical and emotional suffering that came with them. It was the ‘völkische’ and later Nazi war propaganda that appealed to German men, who at the time held a greater position of sociopolitical power than German women. In their eyes, war became a means of restoring lost honour and could not be seen as negative.

National Socialist propaganda poster

National Socialist propaganda poster

Bibliography

Frank, V. (1982). Käthe Kollwitz, Bekenntnisse. Frankfurt am Main: Röderberg Verlag.

Kellner, D. (1983). Expressionism and Rebellion. In S. &. Bronner (Ed.), Passion and Rebellion: The Expressionist Heritage. London: Croom Helm Ltd.

Lenman, R. (1997). Artists and Society in Germany 1850-1914. Manchester: Manchester UP.

Maier, H. (2001). Potential for Violence in the Nineteenth Century: Technology of War, Colonialism, ‘The People in Arms’. Totalitarian Movements and Political Religions, 2(1), 1-27.

Mosse, G. (1964). The Crisis of German Ideology. New York: Schoken Books.

Prelinger, E. (1992). Käthe Kollwitz. New Haven and London: Yale UP.

Pulzer, P. (1997). Germany 1870-1945. Oxford: Oxford UP.

Reinhardt, K. F. (1950). Germany: 2000 Years. California: The Bruce Publishing Company.

Ricoeur, P. (1984). Time and Narrative. Chicago: Chicago UP.

Scheff, T. (2006). Theory of Runaway Nationalism: Love of Country/Hatred of Others. Retrieved March 8, 2009, from http://www.soc.ucsb.edu/faculty/scheff

Scheff, T. (2007). War and Emotions: Hypermasculine Violence as a Social System. Retrieved March 8, 2009, from http://www.soc.ucsb.edu/faculty/scheff

Toolan, M. J. (1988). Narrative: A critical Linguistic Introduction. London: Routledge.

Images

Bild aus den Film Das Vermächtnis mit Archivfilmmaterial von Die Schlacht von Arras

Archivfilmmaterial von Aufmarsch des Rotfrontkämpferbundes

Titelblatt der Zeitschrift Deutschlands Erneuerung. Monatsschrift für das deutsche Volk, 1919 https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Völkische_Bewegung

Potsdamer Platz, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Oel auf Leinwand 1914

https://www.moma.org/audio/playlist/213/2792

Kriegskrüppel, Otto Dix, Oel aus Leinwand 1920

https://www.reddit.com/r/Art/comments/k8lm88/kriegskrüppel_war_cripples_otto_dix_oil_on_canvas/

Selbstbildnis, Kaethe Kollwitz, Holzschnitt 1924

https://www.kollwitz.de/selbstbildnis-kn-203

Propaganda Plakat

https://www.zeitklicks.de/fileadmin/user_upload/epochen/nationalsozialismus/propaganda/plakat.jpg