‘Anyone who claims that Germany was “unprepared” for Hitler’s rise to power is resisting attempts to see this event as the logical climax of German history’

(Wer behauptet, Deutschland sei auf Hitlers Machtübernahme „nicht vorbereitet” gewesen, wehrt sich gegen Versuche, in diesem Ereignis den logischen Höhepunkt der deutschen Geschichte zu sehen)

(Mosse, 1979)

In previous blogs, we have seen that a perspective in which a loss of social connection to others, that legitimized violence, had established itself and fundamentally shaped the history of Western Europe.

This view enabled Roman imperialism and its hierarchical, patriarchal social structure. When Christianity became the Roman state religion in 303 AD, Roman concepts and hierarchical structures were incorporated into the Christian church, so that even after the fall of the Roman Empire, they continued to have a strong influence on the lives of people living in Western Europe. In foreign policy, the struggle for power in Europe can be seen as an imperialist effort. This struggle led to many violent conflicts such as the Thirty Years’ War, the Napoleonic Wars of Liberation and the First World War. Imperialism enabled colonialism, the slave trade and often extreme violence against the colonized peoples. In domestic policy, this view enabled social inequality, which in extreme cases led to uprisings and revolutions such as the Peasants’ War and the French Revolution.

Wars, uprisings and social upheavals traumatized individuals, but also had negative effects on the social relationships between people and society. For example, the extremely violent reaction to the peasant uprising of 1524-25 left the impression that the social structure of society could not be challenged under any circumstances. Many Germans were therefore anxious to avoid a similar social upheaval in Germany after the French Revolution. Mosse describes how later, the part of the German population that felt threatened by industrialization towards the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century called for a revolution that would lead the German nation back to its roots. Like the artists of classicism and romanticism, they did not mean a social restruction but an ‘inner revolution’. Mosse makes it clear that in this case society was to renew itself from within, while the Jews, who were associated with modernity and all its negative effects, were seen as the internal enemy. According to Mosse, Hitler was therefore able to make use of the desire for this inner German revolution and to turn it into an anti-Jewish revolution (Mosse, 1964).

We have seen that the violent conflicts for supremacy in Europe during the Thirty Years’ War were so extreme in some areas of the German principalities that mothers told their children about them in lullabies. At the same time, religious indoctrination meant that grievances and experiences of suffering were rarely expressed, so that traumatic and disturbing experiences could not be processed. The French Revolution brought about social upheaval, with the middle class emerging as a new class whose members had to struggle with the redefinition of their social position and felt insecure and disorientated as a result. After the occupation by Napoleon’s troops at the beginning of the 19th century, which had furthered the sense of humiliation among the German population, the men of the German middle classes were the ones who created and promoted patriotic nationalist propaganda that was intended to mobilize the population for a defensive war. In doing so, the image of the virtuous and valorous German in contrast to the French enemy was established. The extreme changes and social upheavals triggered by industrialisation in Germany increased the feeling of social alienation that affected especially the lower middle class. The feeling of shame and humiliation that the defeat of the First World War triggered and the unconditional conditions of the Treaty of Versailles intensified the already existing loss of connection. Mosse describes how the ‘völkisch’ movement was able to satisfy precisely these emotional needs that arose as a result, as it offered the uprooted a feeling of belonging and reorientation through a connection to nature, to the community of the people and to their history. He describes how the movement developed out of Romanticism at the time of the Napoleonic occupation.

Men like Father Jahn, Arndt and Fichte began to propagate the Volk as the heroic liberator of the Germans during the Wars of Liberation. The experience of German subjugation, triggered by the Napoleonic Wars and reinforced by the Congress of Vienna, gave the idea of the Volk an additional meaning. Opposition to the social chaos of industrialization and urbanization came together with the disappointment experienced in relation to the fruitless efforts to create a unified Germany. Some sought an outlet for their frustrations by seeing the Volk as connected to the cosmos and believing that they saw a true and deeper reality in it. Idealized, the Volk symbolized the longed-for unity that had not been realized in reality, and in the utopian rural-medieval world suggested by the ‘völkisch’ movement, it was possible to escape the turmoil of urban-industrialized life. Mosse mentions writers who spread ‘völkisch’ ideas, such as Berthold Auerbach, Wilhelm Heinrich Riehl and Hermann Löns. This led to the glorification of peasant heroes and often to a fascination with violence.

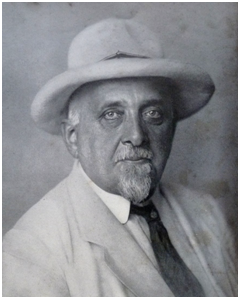

The enemy images included the uprooted proletarians and the Jews as representatives of modern industrial society. Mosse describes how the ideology of the ‘völkisch’ movement developed into a Germanic religion under the influence of two writers of the late 19th century: Paul de Lagarde and Julius Langbehn. As prophets of the ‘völkisch’ movement, they developed concepts of religion, national creativity and education to create a nation structured according to popular principles at a time when Germany was developing into a modern military and economic power. In the process, the fundamental ideas of the ‘völkisch’ movement, the primacy of the people and the abhorrence of the Jews, were further developed. An influential German publisher, Eugen Diederichs, who also published the magazine Die Tat (The deed) from 1912, further contributed to the spread of ‘völkisch’ ideas by reviving the Romantic movement as ‘New Romanticism’. In it, ‘völkisch’ ideas were combined with those of Romanticism. The originally pantheistic vision of the cosmos developed into a pursuit of a Germanic religion, racist ideas based on pseudo-scientific studies were integrated and an urgency to realize the ‘völkisch’ idea was palpable. Mosse highlights that the attitude of Diederichs and that of most of the writers he published was intellectually thoughtful and moderate rather than fanatical, which gave the ‘New Romanticism’ an air of seriousness. It was permeated by a new vital spirituality that opposed the mechanism and positivism of modern society in order to rebuild the German national character, inspired by a desire for unity. According to Mosse, Diederichs’s ‘New Romanticism’ was also an idealism of action that sought concrete means to realize itself. Diederichs was very interested in German cultural history and published old German myths and legends to make the spirit of the people accessible to all. The sun was seen as the true god of the Germanic peoples and sun worship became an important part of religious rituals. Since the youth movement participated in these rituals, folk music and dance were the main focus. Mosse emphasizes that Diederichs and his colleagues did not really hold anti-Semitic ideas, but practiced an elitist mindset and believed that a small group of chosen ones, of which they counted themselves, were destined to revive the cultural life of Germany.

The enemy images included the uprooted proletarians and the Jews as representatives of modern industrial society. Mosse describes how the ideology of the ‘völkisch’ movement developed into a Germanic religion under the influence of two writers of the late 19th century: Paul de Lagarde and Julius Langbehn. As prophets of the ‘völkisch’ movement, they developed concepts of religion, national creativity and education to create a nation structured according to popular principles at a time when Germany was developing into a modern military and economic power. In the process, the fundamental ideas of the ‘völkisch’ movement, the primacy of the people and the abhorrence of the Jews, were further developed. An influential German publisher, Eugen Diederichs, who also published the magazine Die Tat (The deed) from 1912, further contributed to the spread of ‘völkisch’ ideas by reviving the Romantic movement as ‘New Romanticism’. In it, ‘völkisch’ ideas were combined with those of Romanticism. The originally pantheistic vision of the cosmos developed into a pursuit of a Germanic religion, racist ideas based on pseudo-scientific studies were integrated and an urgency to realize the ‘völkisch’ idea was palpable. Mosse highlights that the attitude of Diederichs and that of most of the writers he published was intellectually thoughtful and moderate rather than fanatical, which gave the ‘New Romanticism’ an air of seriousness. It was permeated by a new vital spirituality that opposed the mechanism and positivism of modern society in order to rebuild the German national character, inspired by a desire for unity. According to Mosse, Diederichs’s ‘New Romanticism’ was also an idealism of action that sought concrete means to realize itself. Diederichs was very interested in German cultural history and published old German myths and legends to make the spirit of the people accessible to all. The sun was seen as the true god of the Germanic peoples and sun worship became an important part of religious rituals. Since the youth movement participated in these rituals, folk music and dance were the main focus. Mosse emphasizes that Diederichs and his colleagues did not really hold anti-Semitic ideas, but practiced an elitist mindset and believed that a small group of chosen ones, of which they counted themselves, were destined to revive the cultural life of Germany.

According to Mosse, it was this elitist attitude that made it impossible for them to gain a truely large following and thereby bring about a change in society. The National Socialists, on the other hand, were later able to exploit the ideological basis laid by the ‘Völkisch’ Movement and the ‘New Romanticism’ for their own ends. What began as a passion to change society turned over time into a glorification of violence. Hitler would later call this desire “the heroic will to serve the people”. Diederichs’ movement, which was initially anti-intellectual, was later driven by the Nazis to such an extent of irrationality that it became understandable to the large masses who could be mobilized by its ideas.

Mosse provides a detailed description of how the ‘völkisch’ ideas established themselves within various groups in Germany and Austria and spread to such an extent that they enabled the Nazis to seize power in 1933. The adoption of ‘völkisch’ ideas within the educational system, the youth movement, by professors, students and organizations such as the Farmers’ League, the Pan-German League, war veterans such as the Stahlhelm, the German National Commercial Assistants’ Association (DHV) and by the conservative German National People’s Party (DNVP) played, according to Mosse, a crucial role in this.

Mosse’s detailed description is presented here in a summarized form, as it makes clear how a distorted worldview that had developed from an unsatisfied need to belong was able to spread and develop to such an extent that it enabled the institutionalized and collective violence of the Nazi regime.

The education system and the youth movement.

By combining the ‘völkische’ ideology with widespread efforts to reform schools, ‘völkisch’ ideas were institutionalized and schools were built according to ‘völkisch’ designs and principles. Mosse points out that due to a shortage of jobs at universities, frustrated academics had to work as high school teachers, to whom ‘völkisch’ orientation gave a new perspective. The racist/‘völkisch’ attitude of this professional group is documented by studies which show that from 1889 to 1933 the most frequent contributions to anti-Semitic magazines were made by teachers. While there were large regional differences between schools and school systems, an analysis of German history books shows that from the beginning of the 19th century onwards they contained all the features of Germanic ideology that were necessary for the spread of ‘völkisch’ ideas. The importance of school indoctrination in this context is also illustrated by the statement of the American historian Fritz Stern, who explained that the thousand teachers who were followers of Lagarde and Langbehn in their youth were as important to Hitler’s rise to power as the financial support he received from German entrepreneurs. Mosse describes how students were made familiar with the ‘völkisch’ ideology through their textbooks, the curriculum and their teachers’ dream of restoring the frustrated glory of the German people, and how these students later joined the youth movement. This had developed from a small hiking club founded in 1901 and grew so quickly that by 1911 it already had 15,000 German youths. The movement embraced the ethical and aesthetic values of the ‘völkisch’ ideology with enthusiasm and, according to Mosse, can be seen as a radical expression of the new romanticism that permeated the younger generation. Activities of the youth movement included hiking and polyphonic singing, visiting German communities abroad and celebrating rites of Germanic origin. Mosse emphasizes that singing folk songs and roaming the countryside were not only romantic forms of expression, but that both created a sense of meaningful community through the fusion of nature and tradition, a community of soul that gave members a sense of belonging. In the youth movement, the Bund formation developed based on leadership, people and community, while the youth movement’s ‘völkisch’ orientation of thought was linked to a rejection of the parliamentary process. Whole generations of German youth instead viewed the Bund as the real form of political and social organization in line with New Romanticism and Germanic beliefs. According to Mosse, while there is no direct connection between the youth movement and National Socialism, the youth movement and the ‘völkisch’ ideology that was practiced and spread through it contributed significantly to preparing the young generation for the National Socialist ideology that followed.

Mosse makes it clear that teachers, students, school reformers and the youth movement contributed to the institutionalization of ‘New Romanticism’. Through them, entire generations grew up believing that only the identification with the people expressed in ‘völkisch’ ideology could be the solution to the German crisis.

Mosse makes it clear that teachers, students, school reformers and the youth movement contributed to the institutionalization of ‘New Romanticism’. Through them, entire generations grew up believing that only the identification with the people expressed in ‘völkisch’ ideology could be the solution to the German crisis.

Students and Professors

At the beginning of the 19th century there had been a strong right-wing movement among German students, which, led by Father Jahn, culminated in the burning of non-Germanic books during the Wartburg Festival. While this tendency to the right briefly declined around 1848, the students of the 1880s had resumed the extreme right-wing political direction. According to Mosse, it was the disappointment that the unification of Germany had not been achieved after the revolution of 1848 and that when it was finally achieved in 1870 by Bismarck, it was not an event in which the whole population was emotionally involved. Mosse points out that 90% of the students came from the middle class, which at that time had to struggle for its economic, social and political position because access to academic careers was limited. In this context, Jews were seen as rivals, anti-Semitic feelings were intellectualized, and anti-Semitism became the most direct expression of ‘völkisch’ conviction among students. A racist attitude also spread in the fraternities, extending from Linz and Vienna to the whole of Germany, and according to Mosse, students and professors at German universities became the pioneers of the ‘völkisch’ movement. Among the latter, there were some who saw themselves as prophets of nationalism, such as Heinrich von Treitschke, professor of history at the University of Berlin, who used his academic position for patriotic purposes and whose cultural history book ‘German History in the 19th Century’ became of great importance for the ‘völkisch’ movement.

Organizations that enabled the spread of the ‘völkisch’ ideologies.

Mosse describes how the Bund became the ideal structure of an elite society for many ‘völkisch’ thinkers. A number of organizations formed themselves according to the structure of the Bund, that is, they were based on the leadership principle and the close cohesion of male interests. The NSDAP also adopted this structure in its early phase.

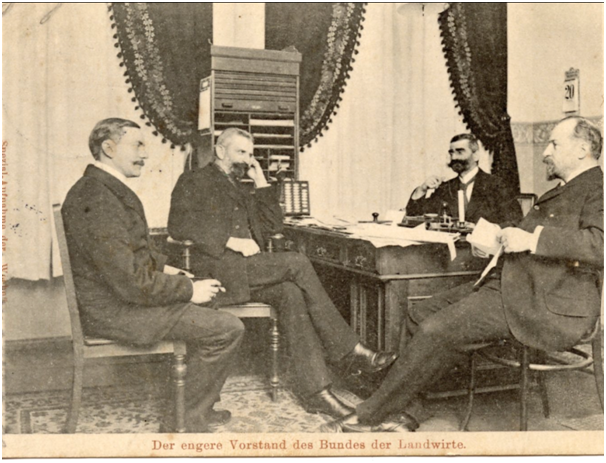

Der Bund der Landwirte (The Farmers’ Association)

Der Bund der Landwirte (The Farmers’ Association)

One of the nationalist organizations was der Bund der Landwirte, which was founded in 1893 and represented the interests of farmers and agriculturists, a professional group that felt its livelihood was threatened by the rapid industrialization of Germany. Der Bund der Landwirte relied on the Germanic principle of blood and soil and consisted of both small farmers and large landowners who shared a strong anti-Semitic attitude. The organization was politically close to the conservative parties and their interests were represented by them.

‘Alldeutscher Verband’ (Pan-German League)

From the 1890s onwards, a number of organisations had attempted to implement the essence of the ‘völkische’ ideology and achieve a unity of the German people. Before World War I, the Pan-German League was one of the most prominent organisations advocating a programme based on ‘völkisch’ ideas.

The ‘Alldeutscher Verband’ organised itself in 1890 as a patriotic group opposing the surrender of Heligoland to England. The members of the League became sponsors of German imperialism from a ‘völkische’ perspective, calling for a real racial and cultural unification of Germany in which the German spirit would play a decisive role in culture, social organisations and politics. While they were initially closer to farmers’ associations than to industry, this changed when Alfred Hugenberg, the former director of Krupp, became a member. The Pan-German League advocated war and rearmament to help heavy industry out of the post-war recession. The members of the Pan-German League were respectable citizens who valued their reputation and, like the industrialists, were anti-communist. Heinrich Class, one of its leading members, called for a German dictatorship in which the ideal society could be realized through the ‘eternal people’.

The ‘Alldeutsche Verband’ supported the spread of an anti-Jewish view within society and spread anti-Semitic teachings. In 1918, the ‘Alldeutsche Verband’ entered into close ties with the ‘Deutsch Nationale Volks Partei DNVP’ (German national peoples party) in order to expand its political power and attack the Republic. Close contacts with the military and the government followed, which enabled the effective spread of its ideological propaganda. Hitler’s seizure of power meant the end of the ‘Alldeutsche Verband’, as its members had joined the National Socialists since the early 1930s. According to Mosse, the Nazis represented for them the logical completion of their own ‘völkisch’ ideas.

The ‘Stahlhelm’

Mosse points out that, as history shows, veterans tend to form right-wing interest groups, especially after a military defeat. The former soldiers want the nation for which they suffered and for which their brothers died to remain unchanged, and they unite to fight for the fatherland for which they risked their lives. The German soldiers faced fundamental changes after their return from the front, as the monarchy had been replaced by a republic. The social unrest and confusion they found aroused in them a strong desire for order and stability. War veterans therefore organized themselves and formed alliances with ‘völkisch’ organizations, thereby gaining enough political power to influence political events. The ‘Stahlhelm’, the largest and best known veterans’ organization, was founded in 1919 with the aim of representing the interests of the fatherland while remaining politically neutral. Elements of ‘völkisch’ thought such as racism and the desire for a social organization of the nation inspired by medieval Germanic society were adopted. With an anti-materialist and anti-Marxist attitude, the ‘Stahlhelm’ was politically close to the ‘DNVP’ and its leader Franz Seldte. In January 1933, Seldte joined the NSDAP-DNVP coalition cabinet and oversaw the integration of the ‘Stahlhelm’ into the NSDAP. He then served as Minister of Labor throughout the Third Reich.

The Deutschnationale Handelsgehilfen Verband DHV (German National Commercial Assistants Association)

The DHV was founded in 1895 to organize industrial employees and was Germany’s largest white-collar union. Like the ‘Stahlhelm’, the DHV considered itself politically neutral at the time, but had developed close ties with the ‘Alldeutsche Verband’ before the war and, like the League, advocated a more militant and imperialist foreign policy. According to Mosse, the ‘völkische’ ideology and anti-Semitism were central to the union’s organizational structure and existence and served to unite and give a common denominator to members of different parties such as the Catholic Center Party and even the Democratic Party. All members advocated an anti-Semitic domestic policy that would solve the problems of the workers and the nation as a whole. The DHV also had other ‘völkisch’ tendencies and close ties to other ‘völkische’ organizations. Mosse describes the DHV’s lower-middle-class members as petty bourgeois, anti-feminist and anti-Semitic, and concerned about their social status, fearing they would sink into the proletariat. They longed for a return to old institutions and conditions and hoped for a revival of medieval guild structures. Although the union was close to many right-wing parties, it was difficult for it to develop close political relations because it had to represent the interests of the workers. However, the NSDAP ‘National Sozialistische Deutsche Arbeiter Partei’ (National Socialist German Workers Party) managed to win over the DHV, take over its organization and integrate it into the ‘National Sozialistische Arbeiter Front’ (National Socialist Labor Front) after 1933. Mosse makes it clear that the Bohemian-Austrian branch of the DHV was politicized from the very beginning and represented a radical perspective. This branch was incorporated into the NSDAP as early as 1920.

The ‘Deutsch Nationale Volks Partei’ DNVP (German National People’s Party)

Mosse describes how conservatives in Germany formed links with nationalist organizations during the 1880s and 1890s, when economic difficulties and recessions plagued them. After the war, the DNVP, founded in 1918, became the most important and most respected party of the right-wing political parties. They included all those for whom private property, the state and the church were sacred, and until 1928 loyalty to the German Kaiser was also maintained. The party represented the interests of the ‘Bund der Bauern’ and formed an alliance with the ‘Alldeutsche Verband’ in foreign policy.

Mosse describes how conservatives in Germany formed links with nationalist organizations during the 1880s and 1890s, when economic difficulties and recessions plagued them. After the war, the DNVP, founded in 1918, became the most important and most respected party of the right-wing political parties. They included all those for whom private property, the state and the church were sacred, and until 1928 loyalty to the German Kaiser was also maintained. The party represented the interests of the ‘Bund der Bauern’ and formed an alliance with the ‘Alldeutsche Verband’ in foreign policy.

Their anti-Semitic attitude was evident in their Tivoli program, in which they defamed Jews as the opponents of conservative principles. According to Mosse, after 1918, its members’ fear of a Marxist revolution was combined with a fear of Jewish domination, and while they themselves acted as respected figures, they spread racist propaganda portraying Jews as the real obstacle to achieving an ideal German society. In 1928, Alfred Hugenberg became chairman of the DNVP. Hugenberg was a founding member of the ‘Alldeutsche Verband’ had headed the Krupp company responsible for German arms production for ten years, and had additionally built a media empire to spread his radical nationalist ideas. Hugenberg had support from both industry and culture, and in his obsessive fear of the left he also turned to the ‘Stahlhelm’ and the NSDAP. Mosse describes Hugenberg as a rival of Hitler, whose party ultimately lost out to the NSDAP due to its elitist attitude, as it did not appeal to the masses like the latter. Mosse emphasizes that the DNVP must be seen as one of the most important transmitters of popular thought and ‘völkisch’ ideology, as it had great resources because of its close ties to industrialists and bankers and was able to reach many voters due to its seriousness. According to Mosse, it was the seriousness of the DNVP that helped Hitler to power, while the party itself came away empty-handed.

Mosse illustrates how the ‘völkisch’ ideology spread among respected conservatives, veterans, and employees, and was thereby strengthened and adopted by the emerging Nazi Party. Most of the ‘völkisch’-minded groups mentioned here initially collaborated with the Republic, with the intention of replacing it with another political order that would be more in the interests of the people. They facilitated the rise of the Nazis, even if they did not support their racist extremism, and initially welcomed their anti-republican, anti-Marxist contribution. If they turned against the Nazi Party, it was only to defend their own political supremacy. Mosse emphasizes that within the groups committed to the ‘völkisch’ ideology, over time, a desire arose for a political system that was based on old customs, that would revitalize the people, and establish a properly Germanic form of government. At the center of this vision, according to Mosse, was the figure of a messianic leader (Mosse, 1964).

Mosse’s descriptions clearly show the causal relationship between experiences of frustration, shame, humiliation and a sense of uprootedness and a willingness to internalise an ideology that promised emotional compensation for the emotional losses, even if this involved violence. This can be observed in the context of German history both in individuals and in smaller and larger social groups. For example, Mosse describes the two ‘völkisch’ writers Langbehn and Lagarde as frustrated academics who bore a grudge against the established educational system from which they were excluded and who compensated for their resulting personal and professional degradation with an inflated sense of self-worth. Mosse describes Lagarde as angry and Langbehn as mentally unstable with strong dictatorial tendencies (Mosse, 1964). As already mentioned, many high school teachers were frustrated academics; Farmers, craftsmen and small employees felt their social and economic position threatened by the social changes brought about by the Industrial Revolution; men of the German middle class felt insecure as members of a new social class since the French Revolution. German unification in 1870 had not fulfilled the emotional expectations of those who had fought for it for so long; the defeat in the World War was experienced by many as shameful and the conditions of the Treaty of Versailles as humiliating; the economic recession and inflation of the post-war years were experienced by many as an existential threat and the social unrest they triggered reinforced this impression.

In an atmosphere of fear, frustration, humiliation, shame, confusion and alienation, it became possible to mobilize these strong emotional needs for right-wing radical and violent politics.

Bibliography

Mosse, G. (1964). The Crisis of German Ideology. New York: Schoken Books.

Mosse, G. L. (1979). Ein Volk, ein Reich, ein Führer: deutsch völkische Ursprünge des Nationalsozialismus (Deutsche Erstausgabe ed.). Königstein: Athenäum Verlag.

Stern, Fritz (1961) The Politics Of Cultural Despair: A Study In The Rise Of The Germanic Ideology. Berkeley: University of California Press

Images

https://www.amazon.de/Rembrandt-Als-Erzieher-Einem-Deutschen/dp/0274301520

https://www.wikiwand.com/en/Eugen_Diederichs#Media/File:Diederichs,Eugen_1867-1930.jpg

Lager der Bündischen Jugend in Berlin-Grunewald (Mai 1933) https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bündische_Jugend#/media/Datei:Bundesarchiv_Bild_102-14642,_Berlin-Grunewald,_Zeltlager_der_bündischen_Jugend.jpg

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bund_der_Landwirte#/media/Datei:Hahn_075.jpg

Altdeutsche Blätter

Der Stahlhelm in Uniform, c. 1934

Logo der DNVP

Antisemitische Wahlwerbung zur Reichstagswahl 1930

Wappen der NSDAP