‘We need future-oriented perspectives, which do not deny the traumas of the past but transform them into possibilities for the present’

‘We need future-oriented perspectives, which do not deny the traumas of the past but transform them into possibilities for the present’

Braidotti 2006

In the first part of this blog series, we examined trauma and trauma-like experiences by referring to neurobiological, psychotherapeutic and sociological studies to illustrate how violence is made possible by a person’s lost connection to themselves and to their natural and social environment. It became clear that the human physical, psychological and social makeup enables and also makes a close relationship to the self and others necessary and that this relationship can be broken by traumatic or trauma-like experiences. For the individual, it was the unconscious and constant nature of the memory of a life-threatening event that impaired the ability to stay connected to the changing reality of life. In the social sphere, it was experiences of shame, loss of a caregiver and humiliation that, if left unprocessed, can trigger the impression of a lost connection, and in the societal context, it was social crises that caused a feeling of social uprootedness and thus a loss of collective identity. We have also seen how these losses of connection are, at the respective levels, causally related to violence: in that they themselves lead to, promote, enable or permit violent action.

Building on this understanding, in the second part of this blog series we examined German history to trace how the loss of social and societal connection developed and intensified in this specific context, culminating in the spread of a distorted ideology that facilitated the collective, institutionalized and industrialized violence of National Socialism. We examined certain points in German history that were particularly affected by social crises and analyzed cultural productions from these times to determine to what extent and in what form social and societal loss of connection intensified over time.

In the last and third part of this blog series, we will examine how lost connections can be restored and what we can learn from the extreme violence of German National Socialism to enable peaceful coexistence in harmony with ourselves and our social and natural environment in the future.

The re-establishment of lost connections

Trauma therapy

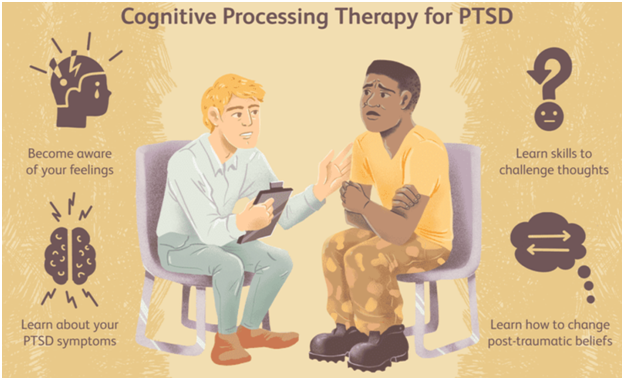

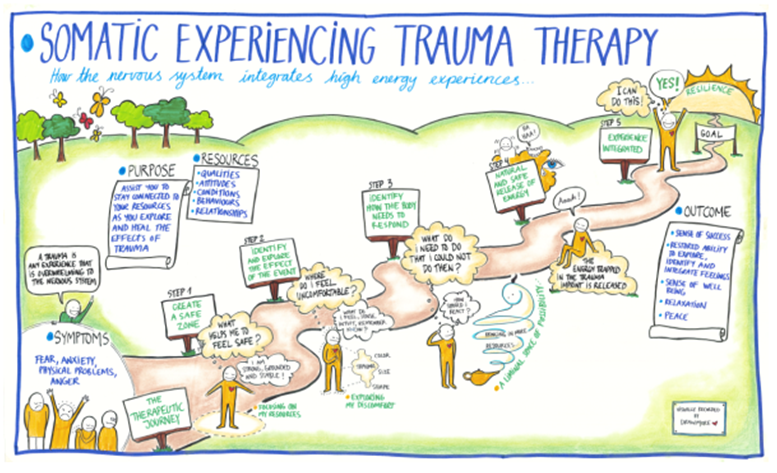

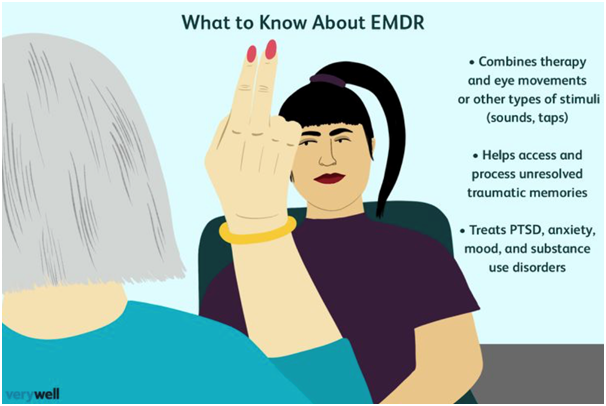

At the level of individual psychology, the individual’s relationship to the self, others and the environment, which is interrupted by the constantly recurring traumatic memory, can be restored through trauma therapy. The traumatic memories are awakened in various ways, under circumstances that make it possible to re-experience the events that were once experienced as threatening as no longer threatening. The synaptic connections that enable the memory to persist are then constructed and maintained by proteins and not by prions (pathological proteins), so that the synapses can decay naturally when the no further stimulation occurs. Forgetting an event that is no longer relevant becomes in this way possible again and the blockage to a connection with the social and natural environment is removed. As mentioned in the genealogy of the trauma concept, hysteria and dissociative disorders were already recognized in the 19th century and treated with therapeutic methods, some of which, with the exception of psychoanalysis, involve the use of hypnosis. Since the 1980s, additional methods have been developed that often use cognitive and non-cognitive elements in combination. I will briefly discuss a number of therapy methods that can enable the processing of traumatic experiences. My focus will be limited to those methods that illustrate how lost connections can be restored.

The most relevant trauma therapy methods in this context are:

The most relevant trauma therapy methods in this context are:

1) Traumatic Incident Reduction: A method that takes the patient through a revision process back to the traumatic experience and promotes processing of the trauma through cognitive understanding. Here, the lost reference to oneself is addressed by understanding one’s own fear and its causes.

2) Somatic Experiencing (Levine 1997): A method that restores the natural ability of the autonomic nervous system to regulate itself after it has been disrupted by a traumatic experience. The therapy involves the person being treated observing their own physical and emotional experience under guidance in order to recognize the type and extent of dysregulation in the body as a result of trauma. All changes in the body that occur during the regression process are viewed as clues and tracked. Resources are set up that enable the autonomic nervous system to return to a regulated state. The patient is briefly returned to the unregulated state and supported in repeatedly returning to a regulated state (pendulation) until the energy blocked by the traumatic memory is discharged and the nervous system’s natural ability to self-regulate is restored. The patient’s relationship to himself or herself, which was disturbed by dysregulation, is made possible by a return to the regulated state (Levine, 2005).

3) EMDR: Eye Movement Desensitization Reprocessing. For EMDR therapy, methods of traditional psychological therapy are initially used as part of the treatment. During the regression into the traumatic memory, however, the reprocessing of the stored traumatic memory is stimulated by regular eye movements from left to right or by concentrating on a regular pulsating rhythm (Bergmann, 2000). The regular movement of the eyes and the pulsating rhythm simulate the processing of experiences in sleep through dreaming. This means that the traumatic experience is processed in a similar way and can be re-stored as a non-threatening event. The traumatic memory is in this way converted into a non-traumatic memory and can be forgotten. This enables a return to an undisturbed connection to the present.

3) EMDR: Eye Movement Desensitization Reprocessing. For EMDR therapy, methods of traditional psychological therapy are initially used as part of the treatment. During the regression into the traumatic memory, however, the reprocessing of the stored traumatic memory is stimulated by regular eye movements from left to right or by concentrating on a regular pulsating rhythm (Bergmann, 2000). The regular movement of the eyes and the pulsating rhythm simulate the processing of experiences in sleep through dreaming. This means that the traumatic experience is processed in a similar way and can be re-stored as a non-threatening event. The traumatic memory is in this way converted into a non-traumatic memory and can be forgotten. This enables a return to an undisturbed connection to the present.

Since most trauma therapy methods require cognitive or implicit regression to the traumatic experience, the following four observations should be taken into account in this context:

Since most trauma therapy methods require cognitive or implicit regression to the traumatic experience, the following four observations should be taken into account in this context:

1) Memories are associative and usually linked to spatial experiences.

2) Memories are mood-congruent (LeDoux 2002) and are therefore easier to awaken if the emotional state at the time of retrieval is similar to that of the original event.

3) Emotional excitement tends to strengthen the ability to remember.

4) Prolonged excitement and stress can have the opposite effect and impair the ability to remember (LeDoux 2002: 222-223).

Loss of connection in the social and societal context and its reversal

As already mentioned, a loss of connection can also occur in the social environment and be triggered by the loss of an important reference person or by experiencing shame and humiliation. By acknowledging these emotions to oneself and others, the lost reference can be restored.

As we have seen, a loss of connection can also occur in a social context due to social crises, which are triggered by revolution and war, for example, and can leave behind a loss of social belonging and a feeling of social uprootedness. Here too, the recognition of a crisis experienced can enable a positive processing and thus restore the connections that are important in a social context. Cultural productions such as songs and pieces of music, pictures, sculptures, literature, dance, plays and films can play an important role in this context, as they enable communication in a social context through which such recognition can take place.

Butoh Tänzer

Butoh Tänzer

Bibliography

Bergmann, U. (2000). ,Further thoughts on the Neurobiology of EMDR: The Role of the Cerebellum in Accelerated Information Processing’. Traumatology, 6, 175-200.

Braidotti, R. (2006). Transpositions: On Nomadic Ethics. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Levine, P. (1997). Waking the Tiger: Healing Trauma: The Innate Capacity to Transform Overwhelming Experiences. Berkeley California: North Atlantic Books.

Levine, P. (2005). Healing Trauma. Boulder: Sounds True.

LeDoux, J. (2002). The Synaptic Self. New York: Penguin books.

Images

https://pixelsandwanderlust.com/perspective-in-photography/?utm_content=cmp-true

https://www.verywellmind.com/cognitive-processing-therapy-2797281

https://carolinejwalker.com/somatic-experiencing/

https://www.verywellhealth.com/emdr-therapy-5212839

Introduction to the World of Butoh