As we saw in the second part of this blog series, the violence of German National Socialism was made possible by the fact that a loss of connection existed on many levels and increased over a long period of time. The emotional needs that arose as a result could be ideologically seized upon and politically manipulated to promote a system in which violence was institutionalized and industrialized.

The extreme extent of this violence makes it clear how important it is that a loss of connection in the individual, social and societal context is recognized and processed in such a way that those connections are restored. Only in this way can violence be prevented in the future and the cycle of violence and trauma be broken.

The good news is that the tendency to connect is a natural given. There is a wealth of evidence for this within neurology, psychology and psychotherapy, sociology, anthropology, archaeology and behavioral research.

This includes the plasticity of the human brain, which enables us to be present in the flow of the ‘here and now’ through constant adaptation.

In his many years of therapeutic practice, Rogers observed that human nature is based on a positive and social orientation (Rogers, 1961).

“One of the most revolutionary concepts to grow out of our clinical experience is the growing recognition that the innermost core of man’s nature, the deepest layer of his personality, the base of his animal nature’, is positive in nature- is basically socialized, forward-moving, rational and realistic……”

(Rogers 1961)

Collins’ theory of interaction rituals, in which members of a group tune into their biological micro rhythms in such a way that they are strengthened and trigger an amplification of the emotional energy of all those involved (Collins, 2004), also confirms this predisposition. The fact that people tend to build positive relationships with one another rather than interacting violently is also evident in studies that show that soldiers usually deliberately miss their targets during operations and show a strong physical aversion to killing (Collins, 2008).

Our basic genetic predisposition to empathy, friendship, cooperation and social learning (Christakis, 2019) also confirms this tendency.

‘We have an evolved capacity (using cooperation, friendship and social learning) to very deftly respond to the myriad circumstances we face, to manifest a kind of bounded flexibility shaped by our genes’

(Christakis 2019)

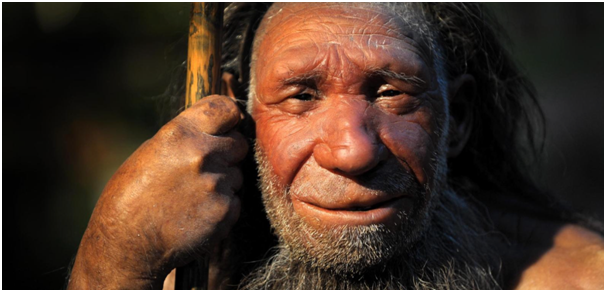

In addition, there are findings from cultural anthropology, archaeology and human paleontology that show that humans have lived a life of peace and social equality for most of their existence on earth. (Fry, 2007) During this time, people lived as nomads in loose groups and made their living by hunting and gathering. Fry emphasizes that the individual members of the groups were relatively autonomous and equal, there was hardly any group leadership and sharing and cooperation were the predominant aspects of the hunter-gatherer ethos. According to Fry, the loose groups of nomads were not closely connected, but in a flexible structure in which membership was constantly changing (Fry, 2007). This flexible, fluid nature is reminiscent of the plasticity of the human brain, which enables us to adapt to a constantly changing environment and thus relate to and stay connected with that environment. At this level, life in the loose hunter-gatherer groups corresponded to the physiological characteristics of humans.

In addition, there are findings from cultural anthropology, archaeology and human paleontology that show that humans have lived a life of peace and social equality for most of their existence on earth. (Fry, 2007) During this time, people lived as nomads in loose groups and made their living by hunting and gathering. Fry emphasizes that the individual members of the groups were relatively autonomous and equal, there was hardly any group leadership and sharing and cooperation were the predominant aspects of the hunter-gatherer ethos. According to Fry, the loose groups of nomads were not closely connected, but in a flexible structure in which membership was constantly changing (Fry, 2007). This flexible, fluid nature is reminiscent of the plasticity of the human brain, which enables us to adapt to a constantly changing environment and thus relate to and stay connected with that environment. At this level, life in the loose hunter-gatherer groups corresponded to the physiological characteristics of humans.

All these observations indicate that we are physically, psychologically and emotionally designed to be connected to ourselves, our social environment and our surroundings. It is therefore only necessary to remove the blockages to this given predisposition so that nothing stands in the way of our inclination to connect.

All these observations indicate that we are physically, psychologically and emotionally designed to be connected to ourselves, our social environment and our surroundings. It is therefore only necessary to remove the blockages to this given predisposition so that nothing stands in the way of our inclination to connect.

However, the bad news is that, as the quote from Aristotle shows, a perspective has been established in Europe for over 2000 years that – based on fear – denies the social equality and interconnectedness of all people and thereby legitimizes and enables violence.

Christakis explains that while our species has developed cognitive systems to quickly recognize and maintain alliances, these systems can also be abused and used to form the basis for violent acts (Christakis, 2019).

Rogers explains that people only tend to engage in constructive social action when they are in touch with themselves and their own experiences, while people who lack such awareness are rightly to be feared (Rogers 1961).

In addition, according to Louis Cozolino, experiences of fear are experienced more intensely and forgotten more slowly than positive experiences (Cozolino 2014), so that a perspective based on fear can easily arise.

Fry’s studies attest to an increase in violence in early history. He describes how social organization developed from loose small groups of hunters and gatherers (25-50 members) to tribes (100 or more people), principalities and later states. While the small groups of hunters and gatherers were politically and socially egalitarian and without direct leadership, this social organization changed with the agrarian revolution and the associated sedentary lifestyle. Tribes were formed in which people lived in settlements and practiced both horticulture and animal husbandry.

While leadership roles developed at this time, they were initially weak, meaning that leadership was achieved through persuasion and example, the social organization of the tribes was largely egalitarian, but there were already divisions into subgroups based on kinship (clans). The larger tribal societies or principalities that developed subsequently, however, had a much more pronounced social hierarchy. Chiefs or princes were entitled to privileges that were appreciated by the citizens.

While leadership roles developed at this time, they were initially weak, meaning that leadership was achieved through persuasion and example, the social organization of the tribes was largely egalitarian, but there were already divisions into subgroups based on kinship (clans). The larger tribal societies or principalities that developed subsequently, however, had a much more pronounced social hierarchy. Chiefs or princes were entitled to privileges that were appreciated by the citizens.

The economies of the large tribal societies or principalities were often based on agriculture or fishing. As late as 5,000 or 6,000 years ago, some early chiefdoms or principalities underwent further organizational changes and the first states emerged.

The economies of these early states were based on agriculture, the rulers exercised more coercion than the chiefs or princes, economic specialization, social class distinction, centralized political and military organization, the use of writing and mathematics, urbanization, large-scale irrigation of crops, and the development of bureaucracy became the hallmarks of both ancient and more modern states. Fry explains how conflict and violence changed as sociopolitical complexity developed. Among simple nomadic gatherers and hunters, conflicts arose only between the individuals involved, which is confirmed by the fact that there are no archaeological finds indicating warfare during this period. According to Fry, conflict and violence increased as social segmentation increased. Thus, a murder within a tribe was felt as a loss not only to the victim’s immediate family but more generally to members of the clan. In seeking revenge, the victim’s larger kin organization could target anyone belonging to the murderer’s social segment. This form of ‘social substitutability’ (Kelly) enabled feuds. Among nation-states, social substitutability could lead to war, as an act of violence provoked retaliation not only against the actual perpetrators but against anyone perceived to be a member of the same national or religious group as the attackers. As states developed, archaeological records often show an increase in the frequency and intensification of wars, a phenomenon often exacerbated by population pressure or environmental changes (Fry, 2007).

The quote from Aristotle from 400-300 BC, therefore, reflects the social segmentation of the ancient Greek state. The causal relationship between this segmentation and violence becomes clear, as the perspective that divides people into two different groups enables the legitimization of violence.

It is this perspective of social segmentation or division that has shaped our history and on which the politics and economics of our society are based that we must revise if we want to enable truly peaceful coexistence. Since we are predisposed to live in relationship and harmony with ourselves and others, there are always efforts that run counter to social segmentation, such as the idea of freedom and equality that inspired the French Revolution. However, since the fundamental perspective on which our Western society is built is never really critically questioned and revised, these efforts cannot be realized and instead a distortion of the original intentions occurs.

It is this perspective of social segmentation or division that has shaped our history and on which the politics and economics of our society are based that we must revise if we want to enable truly peaceful coexistence. Since we are predisposed to live in relationship and harmony with ourselves and others, there are always efforts that run counter to social segmentation, such as the idea of freedom and equality that inspired the French Revolution. However, since the fundamental perspective on which our Western society is built is never really critically questioned and revised, these efforts cannot be realized and instead a distortion of the original intentions occurs.

The history of the Christian church is a good example in this context. While equality and charity are the basis of the teachings of Christianity, after the fall of the Roman Empire the Catholic Church became an instrument of power that adopted the hierarchical structure of antiquity and propagated it within society.

The fear-based perspective, which no longer sees the equality and interconnectedness of all people, is the basis for conflict on both an interpersonal and political level. Only such a perspective made colonialism and racism possible, and the level of violence that was and is legitimized by this perspective is limitless unless it is restricted by a moral and ethical stance. The violence of German National Socialism, which was used against all those who were classified as ‘others’, clearly shows the serious consequences that such a perspective can have.

Bibliography

Christakis, N. A. (2019). Blueprint, The Evolutionary Origins of a Good Society. New York: Little, Brown Spark.

Collins, R. (2004). Interaction Ritual Chains. Princeton: Princeton UP

Collins, R. (2008). Violence. Princeton: Princeton UP.

Cozolino, L. (2014) The Neuroscience of Human Relationships. New York: Norton.

Fry, D. P. (2007). Beyond War. New York: Oxford UP.

Jung, C., & Sparenberg, P. (2012). Cognitive perspectives on embodiment. In S. C. Koch, T. Fuchs, M. Summa, & C. Müller (Eds.), Body Memory, Metaphor and Movement (pp. 141-154). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Images

https://www.welt.de/wissenschaft/article118202099/Jaeger-und-Sammler-fuehrten-keine-Kriege.html

http://www.terra-human.de/kulturelles/hoehlenmalerei.htm

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stammesgesellschaft#/media/Datei:Catlinpaint.jpg

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stammesgesellschaft#/media/Datei:Ingolf_by_Raadsig.jpg