Socio-political background

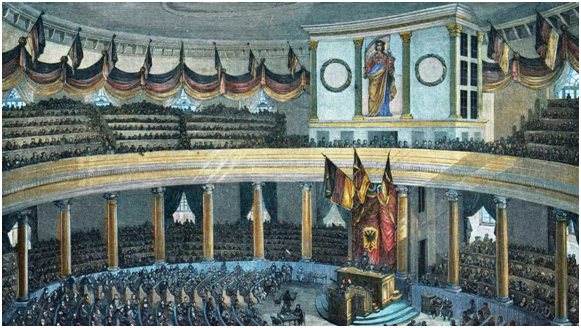

Following Napoleon’s defeat in 1815, the German Confederation was formed, a loose association of 39 states, of which the Kingdom of Prussia and the Austrian Empire were the largest. Pulzer describes how the emergence of an organised liberal movement demanding constitutional reform and greater national cohesion led to revolutions in 1848, which were also fuelled by the revolutionary outbreaks in Paris as well as by widespread economic hardship. After a period marked by barricades and street fighting, the moderate liberal movement, led by the educated middle class, gained the upper hand and sought reforms based on radical democratization, leading to the establishment of the National Assembly. This was the first German parliament, and the members of the assembly attempted to draft a constitution for a democratic and united Germany and to appoint a provisional government. However, as its members could not agree on the nature of German unity or on a general understanding of democratic processes, the National Assembly was dissolved in April 1849, the Confederation of 1815 was restored and the opportunity to establish a united Germany on a democratic basis was lost.

However, according to Pulzer, German national unity, which had been sought since 1848, remained on the public agenda. After a long period of political and diplomatic manoeuvring, which included an invasion of Austria and a brief and victorious war with France, the Prussian Prime Minister Otto von Bismarck succeeded in uniting the German principalities under William I of Prussia in 1870, with the exclusion of Austria. Bismarck had thus demonstrated that it was not democratic parliamentary decision-making, but violence and war that could bring about decisive political change.

However, according to Pulzer, German national unity, which had been sought since 1848, remained on the public agenda. After a long period of political and diplomatic manoeuvring, which included an invasion of Austria and a brief and victorious war with France, the Prussian Prime Minister Otto von Bismarck succeeded in uniting the German principalities under William I of Prussia in 1870, with the exclusion of Austria. Bismarck had thus demonstrated that it was not democratic parliamentary decision-making, but violence and war that could bring about decisive political change.

“The great questions of the time are not decided by speeches or majority decisions, that was the great mistake of 1848 and 1849, but by iron and blood”

Otto von Bismarck 1862

The unified Prussian Empire, which had been the hope of two generations of nationalist publicists, left many dissatisfied because its structure, which consisted of elements of democracy, limited monarchy and autocracy, was politically ambiguous and half-hearted. There was also a lack of symbols that would have reflected a unified collective. Bismarck promoted the fragmentation of parliament, which strengthened the autocratic power of the emperor and led to political frustration among the middle class, while the German Empire developed into an industrial giant whose production capacity increased by 800% between 1870 and 1913 (Pulzer, 1997).

Mosse points out that this extremely rapid industrialization caused social alienation that directly affected a number of social groups such as peasants and artisans, as well as other members of the lower middle class, threatening their social status and livelihood. He underlines how confusing the rapid process of industrialization was for many, causing the sudden shift of the population from the countryside to the cities and social upheavals such as the loss of customs, traditions and crafts. Mosse emphasizes that the demands of an increasingly industrialized society with its new opportunities and limitations fostered the feeling of isolation of the individual and that this isolation and the experience of alienation of people from themselves and their social environment was so severe that many contemporary intellectuals grappled with it, such as the French political scientist Alexis de Tocqueville and the German philosopher and economist Karl Marx. (Mosse, 1964).

Mosse points out that this extremely rapid industrialization caused social alienation that directly affected a number of social groups such as peasants and artisans, as well as other members of the lower middle class, threatening their social status and livelihood. He underlines how confusing the rapid process of industrialization was for many, causing the sudden shift of the population from the countryside to the cities and social upheavals such as the loss of customs, traditions and crafts. Mosse emphasizes that the demands of an increasingly industrialized society with its new opportunities and limitations fostered the feeling of isolation of the individual and that this isolation and the experience of alienation of people from themselves and their social environment was so severe that many contemporary intellectuals grappled with it, such as the French political scientist Alexis de Tocqueville and the German philosopher and economist Karl Marx. (Mosse, 1964).

Socio-cultural background

The increasing sense of alienation and social uprooting had begun to influence cultural productions since the late 18th century. While literature up to this point had spread the ideas of the Enlightenment, the French Revolution in Germany triggered a redefinition of literary theory and practice. The literary scholar Inge Stephan describes how the different reactions to the French Revolution led to the development of classicism, romanticism and Jacobinism.

Only the Jacobin authors were enthusiastic about the French Revolution and aspired to a similar revolutionary transformation in Germany. These authors dealt with social and political grievances, defended the rights of those who were oppressed, propagated equal rights for women and opposed slavery.

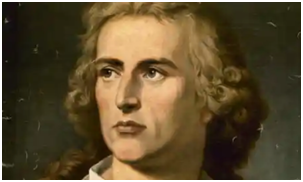

The classical view of literature, on the other hand, which was shaped by Goethe and Schiller, rejected the French Revolution but also advocated a certain social change. While the Jacobin authors dealt with the real needs of their time, the aim of the classicist writers was to achieve an idealization and refinement of human nature and thereby indirectly promote a change in political conditions. The ideal of the Enlightenment, which attributed a social function to art and a calling to improve society, became an important part of German classicism. In 1795, Schiller had defined this social function of culture through the role of the artist, who was to save humanity by restoring balance and beauty in a society shattered by alienation. The Romantic writers also rejected the violent political upheaval that had taken place in France, but like the Classicists, they were critical of German society and, like them, hoped to initiate political and social improvements from within.

Friedrich von Schiller, Portrait

Friedrich von Schiller, Portrait

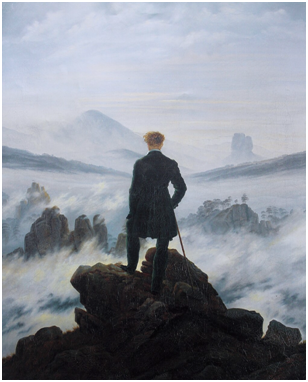

Romanticism was initially a reaction to the rational focus of the Enlightenment and emphasized emotion, intuition and unconscious experience. In contrast to Classicism, in Romanticism art was understood as autonomous and its goal was to create a fusion of art and life, present and past, time and eternity, in which life was understood poetically rather than politically. Through these connections, the experience of alienation was to be overcome and a sense of harmony regained. Stephan describes how the initial optimism of early Romanticism evolved into a darker perspective as the humanist ideals that had inspired the French Revolution were disappointed and increasing industrialization intensified the experience of alienation (Stephan, 2008).

Wanderer über dem Nebelmeer C.D. Friedrich 1818

Wanderer über dem Nebelmeer C.D. Friedrich 1818

Like Stephan, historian Peter Jelavich describes a general disillusionment with humanist values. While German classicist ideals did spread and were applied in the second half of the 19th century, encouraged by the commercialization of culture, they often did so without the ethical values that had inspired them. Jelavich attributes this loss to the failure of the 1848–49 revolution. He describes how classical education was implemented by the Prussian state in the school system in such a way that its initial social and political concerns were lost. At the same time, the commercialization of culture encouraged the writing of popular literature that met the entertainment needs of the general public. The loss of Enlightenment ideals and its ethical values reflected a disconnection from social reality. This disconnection was evident in various areas of German culture, particularly in the aesthetic movements. Jelavich describes how these emerged from a form of sensual classicism, whose main goal was the emancipation and liberation of humanity, and which had been promoted by Heine, Wagner and Nietzsche as a weapon against bourgeois morality and ethics. The aesthetic movements initially had a social and democratic vision and reformist goals, but became increasingly elitist and, since the rejected Christian and bourgeois morality was not replaced by a humanistic ethic, showed a complete loss of moral concerns. The focus on physical beauty combined with social Darwinism led to the development of eugenics, the doctrine of the biological optimization of human genetic material. As an extreme form of aesthetics and vitalist movements, eugenics can be seen as the result of the separation of aesthetics and ethics and as a perversion of sensual classicism (Jelavich, 1979). Eugenics later formed the basis for the National Socialists’ Racial Hygiene Law.

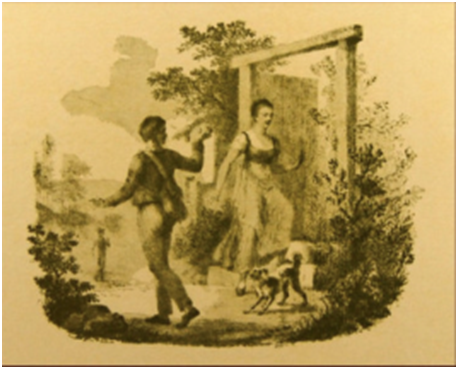

The loss of an idealistic outlook can also be found in the song lyrics of the late Romantic period. Musicologist Barbara Turchin describes a change in the song cycle tradition where this is evident. According to Turchin, the tradition of Wanderlieder cycles was initiated in 1818 by the compositions of Conradin Kreutzer and had subsequently shaped the song cycles of Beethoven, Schubert and Schumann. Originally performed during musical soirees in the early 19th century in private middle-class homes, later song cycles became part of the concert program and were therefore available to a wider public. The theme of the song cycle, the quest of the lonely wanderer, was central to German Romanticism and was used as a metaphor for humanity’s search to restore its lost unity. The goal of this educational and psychological process was to achieve a higher state of unity, symbolized by scenes of recognition, reconciliation or by union with a loved one. Changes in season and landscape symbolize the protagonist’s altered emotional states: the tree represents comfort and spiritual renewal and the relationship with the loved one can be read as a metaphor for connection to society. Turchin refers to the German Romantic poets Hölderlin and Eichendorf and their use of the Romantic wandering theme. According to Turchin, Kreutzer’s original Wanderlieder cycles depict the wanderer’s quest, returning from elation through despair and alienation to a hopeful sense of renewal. In their Romantic approach, which involved the creation of an alternate reality of metaphorical significance, the song cycles expressed the experience of alienation and, through its processing, restored the lost connection. However, this positive conclusion is missing in late Romantic song cycles (Turchin, 1987).

Literary critic Thomas Pfau interprets the texts of late Romanticism as an attempt to convey the experience of historical change from the perspective of the emerging middle class in the 18th and 19th centuries. Pfau describes how the French Revolution, caused by the failure of the Central European aristocracy to fulfil its historical mission, led to a sudden change in the social order from which the bourgeoisie emerged as a new class without social or cultural reference points. This lack of social identity, according to Pfau, led to a feeling of longing for a lost past that triggered an interest in history. Cultural productions responded to the needs of their bourgeois audiences by depicting an imaginary and idealized past that expressed their anti-modern sentiments, met the need for a shared memory, and created a sense of cultural identity (Pfau, 2003).

Literary critic Thomas Pfau interprets the texts of late Romanticism as an attempt to convey the experience of historical change from the perspective of the emerging middle class in the 18th and 19th centuries. Pfau describes how the French Revolution, caused by the failure of the Central European aristocracy to fulfil its historical mission, led to a sudden change in the social order from which the bourgeoisie emerged as a new class without social or cultural reference points. This lack of social identity, according to Pfau, led to a feeling of longing for a lost past that triggered an interest in history. Cultural productions responded to the needs of their bourgeois audiences by depicting an imaginary and idealized past that expressed their anti-modern sentiments, met the need for a shared memory, and created a sense of cultural identity (Pfau, 2003).

Literary scholar Jochen Schulte-Sasse describes how popular literature, which had emerged due to improved education and the advancement of printing technology, responded to the same need. Industrialisation had caused the breakdown of traditional social stratification and a materialist perspective that had led to the decline of clerical authority and the loss of moral standards. The educated middle classes responded by creating and disseminating new moral standards through literary productions. According to Schulte-Sasse, the ideology promoted by popular literature at this time was a form of regressive utopia: anti-modernist and anti-capitalist, and criticising the increase in greed, selfishness, and moral decay that was seen as part of modern life. The depiction of the landscape was ideologically and psychologically important because it represented a return to an agricultural environment and lifestyle lost through industrialisation. This return to the land and the countryside enabled a reconnection with familiar social structures and thus counteracted the feeling of alienation and uprootedness that had been caused by living in the industrialized cities and replaced those feelings with a sense of emotional and social security (Schulte-Sasse, 1983). Mahler’s song cycle, analyzed here as a cultural example, shares some of these characteristics. As with other late Romantic productions, Mahler’s songs, although inspired by personal experience, responded to the bourgeois audience’s need for an alternative reality, as they transport the listener back in time and into the reassuring security of a natural environment away from modern industrialized life.

Cultural sample Die zwei blauen Augen von meinem Schatz from the song cycle Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen by Gustav Mahler 1883-1885

The two blue eyes of my sweetheart,

They sent me out into the wide world.

I had to say goodbye to my dearest place!

Oh blue eyes, why did you look at me?

Now I have eternal sorrow and grief!

I went out in the silent night

over the dark heath.

Nobody said goodbye to me

Goodbye!

My companion was love and sorrow!

There was a linden tree on the street,

There I rested in my sleep for the first time!

Under the linden tree,

It snowed its blossoms over me,

I didn’t know how life would work,

Everything, everything was good again!

Everything! Everything, love and sorrow

And world and dream!

Analysis of the song lyrics of Die zwei blauen Augen von meinem Schatz by Gustav Mahler

The song Die zwei blauen Augen… completes the song cycle Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen (song of a travelling Journeyman ) by Gustav Mahler. Both the text and the musical arrangement were created by Mahler between 1883 and 1885 and the song can be classified as an art song of the late Romantic period.

Die zwei blauen Augen…(The two blue eyes..) is the last of four songs in this cycle and is preceded by the songs Wenn mein Schatz heiratet (When my darling is getting married), Ging heut morgen übers Feld (I went over the field this morning) und Ich hab‘ ein glühend Messer (I have a glowing knife). The first song describes the loss of a relationship due to the marriage of a loved one to another, an experience that sends the protagonist out into the world in search of comfort. The second song expresses the pain of separation, which is intensified by the confrontation with the life-affirming aspects of nature that remain hidden from the wanderer. The third song is about the pain of loneliness, which is compared to a knife in the chest and described as self-destructive and life-threatening. The final song of the song cycle, Die zwei blauen Augen.., reflects the theme of the previous songs in the first verses, but comes to an independent conclusion in the last verse.

If we apply Greimas’ (1966) narrative model to the text of the song, we can clearly identify the lonely wanderer as the subject of the text. The object of his desire is the state of union and connection that he has lost through separation from his beloved. It is difficult to define a ‘perpetrator’ in this text. It could be grief, which is mentioned three times and also described as an imaginary person, but it could also be the wide world, the quiet night or the dark heath, as all seem to stand in the way of the hero’s search for the object of his desire. It is even more difficult to identify a ‘helper’. Possibly it is love, which is mentioned as another person, while the ‘super-helper’ is clearly the tree, because it seems to be endowed with magical power, like in a fairy tale.

According to Genette, in order to examine the three aspects of narrative time – sequence, duration and frequency – the questions ‘When? How long? And how often?’ must be asked. Applied to the text of the song, no time is given for the first action in which the lover dismisses the hero. Only the sequence of events is given, which are thereby linked and which indicate a causal connection. The first chain of events: – the rejection, – the departure, – going out into the night, – the missing of a farewell, expresses how the impression of abandonment and loneliness triggered by the rejection is intensified. The second chain of events: – resting under the linden tree, – finding peace, involves a change from a painful to a pain-free state triggered by resting under the tree. A temporal description is found in verse five through the adverb ‘forever’ in reference to suffering and grief, and a later description of frequency is found in verse twelve which states that the wanderer found sleep ‘for the first time’. Both indications are extreme and contradictory, which contribute to the sense of drama created by the narrative. The general lack of temporal indication gives the feeling that the events are not connected to a concrete situation, indicating that they can be read as a metaphor. A general lack of specific description further contributes to this impression. Not only do we not know when this event happened, we also do not know where it happened, to whom it happened, and why.

If we consider the relationship between structural duration and temporal duration, we find that a certain amount of structural duration is devoted to two events: that of departure in the night and that of finding comfort in sleep under the tree. Both moments are described in detail, while the act of wandering is not mentioned in the text of the song, but only implied. Both events are thus highlighted as contrasting: setting out on the lonely journey and regaining peace in nature.

Very little information is given about the character of the ‘narrative persona’ through adjectives, which, according to Todorov (1981), can provide a description of this. Only the eyes, which represent the beloved, are marked by the adjective ‘blue’, which can be read as a reference to beauty and purity, and a description of the ‘imaginary person’ of grief is given by the adjective ‘eternal’. The protagonist is not described by adjectives, but his character can, according to Toolan, be derived from his actions, whereby it is noticeable that these are reactions to an action of another. The protagonist is thus characterized as a victim because he does not act independently. Here a reversal of gender roles becomes clear: the female protagonist is active and acts independently, while the male protagonist acts passively / reactively and externally determined. The active position of the female person is also reinforced by the fact that she is the initiator of the first chain of events. Represented by her blue eyes, she is also the subject in verses one and four.

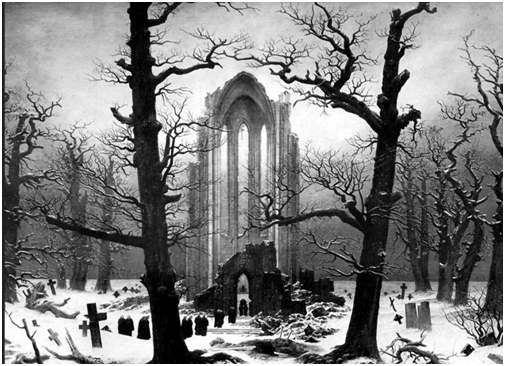

Die Winterreise, Caspar David Friedrich ca. 1827

Die Winterreise, Caspar David Friedrich ca. 1827

Musical analysis of the song Die zwei blauen Augen von meinem Schatz by Gustav Mahler

An analysis of the musical score in its orchestral version in relation to the narrative content of the text provides further information on the interpretation of the song. An audiovisual version of the song can be accessed via the following link:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VTyJ_kUyHGc

The music is composed for an alto or tenor voice with orchestral accompaniment consisting of flutes, an oboe, a French horn, clarinets, a bass clarinet, a harp, violins, a viola, a cello, a bass, horns and a drum. Changes in orchestration and key suggest a structuring into three parts:

1) The pain of separation and the need to leave.

2) Departure and journey.

3) Finding comfort under the tree

While parts 1 and 2 are similar in orchestration but differ in key, part 1 in E minor and part 2 in C major, the change in part 3 to F major is also associated with a change in rhythm and different orchestration, reflecting the turn of events more clearly. What begins as painful seems to resolve as peace is found towards the end. However, a switch back to a minor key after the melody is completed calls this resolution into question and its positive outcome, especially since this final musical segment contains the rhythmic theme with which the song begins and which appears in variations throughout the piece, played by a variety of instruments. This slow and solemn theme gives the impression of a death march, not least because it is very similar to the rhythmic theme of Chopin’s Funeral March, which had appeared in 1839, fifty years before Mahler’s composition. While the song describes the pain of separation and the search for consolation, death seems ever-present from the outset and the inevitable goal of the quest.

The song begins in E minor with a melodic segment in the voice containing the rhythmic theme and a slight up-down-up movement that progressively rises, suggesting a building drama and emphasizing the words that come at the end of each rise. The superlative ‘Allerliebst'(Dearest) at the end of the final rise is particularly prominent. The voice is initially accompanied by the first flute, but later by the first violin, which heightens its emotional impact. The harp accompaniment that follows has an altered harmony and contains dissonant chords that reflect the state of inner conflict described in the text, while the French horn accompaniment is syncopated, disrupting the pulse of the piece and creating a sense of inner turmoil. Music theorist Yonatan Malin highlights the relationship between dissonance through syncopation and romantic longing, both of which developed during the 19th century. According to Malin, a syncopated pulse creates a continued outward movement analogous to the romantic longing for distance. This creates a sense of separation and a movement that reaches into that distance (Malin, 2006).

After a brief change in time signature, the song continues in E minor with a melodic segment similar to the one the song began with, now rising in a wave-like motion – towards the word ‘Leid'(Pain) and falling towards the word ‘Grämen'(Sorrow) . Both words are emphasized and connected by the rise and fall of the melody, suggesting a causal connection. The changes in time signature and key in this section and the inclusion of dissonant sounds further help to express inner conflict and emotional chaos. The first violin accompanies the singing voice, highlighting the emotive content of this section. The rhythmic opening theme is played by the flutes after the melody is completed, reminding us that the protagonist is on his way to his grave. The change to part 2 is marked by a change of key to C and by a steady pulse of drum and Bass, which gives musical expression to the walking movement of the protagonist who has set out on his search. The melody begins with the rhythmic theme as in the previous verses, but this time the accompaniment by flute or violin is missing, reflecting the lack of human accompaniment mentioned in the lyrics of the song. The last part of the rhythmic theme is later accompanied by the horns and then played by the clarinets, creating the impression of an echo and thereby suggesting space. The singing voice then rises and falls in undulating downward movements in chromatic scales. Dissonant sounds and changes in key create the impression of distress as the protagonist enters the dark night The pulse given by the drum and bass continues after the melody has finished, while the rhythmic theme of the funeral march is played by various instruments in minor and major keys with decreasing volume, suggesting a disappearance into the distance, which gives the impression of an expansion in space and time. The lonely wanderer goes out into the wide world and wanders around for a long time. The search and the time needed for this search are thus illustrated in the music, while they were not mentioned in the lyrics of the song.

A change in key and rhythm, as well as sudden unusual single notes in the harp accompaniment, signal the beginning of the third part and bring the listener into a new situation. The pulse of bass and drum stops, indicating that the search is over. The harp accompaniment is now heard in initially incomplete, then completed harmonic broken chords, reflecting nature in its lush, flowing and balanced state and with its potential to provide comfort. The singing voice rises and falls repeatedly in an undulating, up and down motion, creating a sense of well-being, which is reinforced by the violins supporting the singing voice and indicating the return of the previously missed sense of companionship. At the same time, the first horn repeatedly plays a descending scale, illustrating the falling of the blossoms. Again, the singing voice rises and falls but is at odds with all the other instruments when it reaches the word ‘Leben’ (life). This word is thereby both highlighted and suggestively associated with inner conflict. The singing voice continues with a rise and chromatic fall to ‘war alles wieder gut’ (was everything well again), ending on a note that does not resolve the harmony as expected when it reaches the word ‘gut'(well). While the lyrics of the song convey that everything is back to normal, the musical impression undermines and questions this statement. The following melody falls three times, changing key in a variation that creates an A-B-A structure that is circular, indicating that the circle of life is complete. The remaining voice line, ‘Alles! Alles! Lieb ‘und Leid! Und Welt und Traum!’ (Everything! Everything, love and sorrow !And world and dream!)

is slow, monotonous, repetitive and drawn out by rests in each bar, descending incrementally. The broken chord accompaniment in the harp ends in the last bar of the melody, turning into a chord that is repeated with increasing rests and decreasing volume, giving the impression of a heartbeat coming to an end. The musical theme, echoed by the flute, recalls the funeral march that seems to underlie the song. While the entire section is played in pianissimo, the volume drops to ppp at the end. The music thus makes the meaning of the ambiguous text clear. The consolation that the lonely wanderer finds in the shade of the tree is death.

Winterlandschaft, Caspar David Friedrich 1811

Winterlandschaft, Caspar David Friedrich 1811

Conclusions

The song Die zwei blauen Augen von meinem Schatz is one of the Romantic cultural productions that sought to express the experience of alienation and social uprooting felt especially by the male middle class in 19th century Germany. For Gustaf Mahler, who as a Jewish composer was exposed to the growing anti-Semitic climate in Germany and Austria, the experience of social and societal alienation may have been even stronger. The feeling of uprootedness is evident in the lack of clarity and specificity in the lyrics. The song is set in a timeless world that is far removed from the experiences of the 19th century. While this distance illustrates alienation, it also makes it difficult to confront the events that had created this loss, and the felt longing for the lost connection can only be expressed indirectly, through metaphors. Originally, the use of metaphors, which were an essential element of romantic cultural productions, was guided by the intention of indirectly expressing painful experiences in order to enable the restoration of lost connections. However, this intention was lacking in the cultural productions of the late romantic period, which led to a disillusionment with the initial cultural objectives. Painful experiences were expressed indirectly without being processed. The fact that the song Die zwei blauen Augen… belongs to the late romantic period is evident from the fact that the narrative of the lyrics does not have a positive ending. As the musical version makes clear, the longed-for reunion can only be found outside of the reality of life: in death.

The literary scholar Ann Kaplan describes how, at certain historical moments, aesthetic forms emerge that express the fears and fantasies that arise from the repression of crucial historical events that have not been processed. In this context, Kaplan speaks of a phenomenon that she calls a ‘traumatic cultural symptom’ (Kaplan, 2001). The repressed historical event in this context would be, according to Pfau, the feeling of social alienation that the middle class has experienced since the French Revolution. Fears and fantasies triggered by the loss of social and societal reference are represented by the depiction of lost love and the identification with the lonely wanderer. This escape into an alternative reality that is thereby made possible is reminiscent of the dissociative symptoms of post-traumatic disorders. According to Collins, the impression of a loss of social relationships can be experienced as a lack of access to a gain in emotional energy. Longing, expressed in romantic cultural productions, can thus be interpreted as a desire to regain this lost access, motivated by the lack of emotional energy. The passive attitude of the song’s protagonist confirms this lack, since, according to Collins, emotional energy is necessary for active behavior.

Ansicht von Lübeck, Andreas Aschenbach

As mentioned in the last chapter, Scheff describes how unresolved experiences of shame and humiliation can affect gender relations and lead to behavior that Scheff calls ‘hypermasculine’ and ‘hyperfeminine’ respectively. The fact that the gender roles are reversed in the song’s narrative, a feature typical of Romantic cultural productions, reflects a state of imbalance that shows how much the crisis of social alienation had affected the middle-class population. While these productions portray their male protagonists as physically and emotionally vulnerable, passive, suffering and in an extreme state of longing, the narrative is set outside of reality, which can be compared to the dissociative behavior typical of women in response to traumatizing events, as opposed to the male fight-or-flight response.

While Die zwei blauen Augen…, as an art song, was aimed at the educated middle classes, popular literature was accessible to a wider audience, including the lower middle classes. In an attempt to respond to the emotional needs of the readership, popular literature often constructed a distorted worldview (Schulte-Sasse 1983). Mosse describes how the persistent need for collective identification led to a search for lost roots, in which distorted ideas developed, which Mosse summarizes under the term ‘völkisch ideology’ (Mosse 1964). Mosse emphasizes the importance of the connection between the human soul and the essence of nature for this ideology, a perspective that was expanded to describe a relationship between the people and the native landscape. This affinity with nature, especially forests and trees, is the main theme of romantic cultural productions and also the setting for the Wanderlieder cycles. Mosse explains how the ‘völkisch’ ideology evolved over time to include racist perspectives and was elaborated and disseminated after the defeat of the First World War and the establishment of the Weimar Republic, then gaining a political base supported by the majority. Mosse highlights the importance of youth groups, which had developed nationwide with 60,000 members before the war and 100,000 after the war, which promoted forays into nature together with ideologically motivated activities.

Since romantic cultural productions reflected the sense of alienation and confusion felt by many, but without expressing the crises in a way that allowed them to be processed and a collective sense of identity to be restored, the persistent emotional need was open to abuse and, as we will see in the following blogs, enabled the development of racist ideologies and political orientations.

Steglitzer Gruppe um 1930

Steglitzer Gruppe um 1930

Bibliography

Greimas, A. J. (1983). Structural Semiotics: An attempt at a method (Translated by D. Mc Dowell et al. ed.). Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Jelavich, P. (1979). Art and Mammon in Wilhelimine Germany: The case of Frank Wedekind. Central European History, 12(3), 203-236.

Kaplan, A. (2001). Melodrama, Cinema and Trauma. Screen , 42(2), 201-205.

Malin, Y. (2006). Metric Displacement Dissonance and Romantic Longing in the German Lied. Music Analysis, 25(iii), 251-288.

Mosse, G. (1964). The Crisis of German Ideology. New York: Schoken Books.

Mosse, G. L. (1979). Ein Volk, ein Reich, ein Führer: deutsch völkische Ursprünge des Nationalsozialismus (Deutsche Erstausgabe ed.). Königstein: Athenäum Verlag.

Pfau, T. (2003). Lyric Cliche, Conservative Fantasy, and Traumatic Awakening in German Romanticism. The SOuth Atlantic Quarterly, 102(1), 53-92.

Pulzer, P. (1997). Germany 1870-1945. Oxford: Oxford UP.

Scheff, T. (2006). Theory of Runaway Nationalism: Love of COuntry/Hatred of Others. Retrieved March 8, 2009, from http://www.soc.ucsb.edu/faculty/scheff

Scheff, T. (2007). War and Emotions: Hypermasculine Violence as a Social System. Retrieved March 8, 2009, from http://www.soc.ucsb.edu/faculty/scheff

Schulte-Sasse, J. (1983). Towards a ‘Culture’ for the Masses: The SocioPsychological Function of Popular Literature in Germany and the U.S., 1880-1920. New German Critique, 29, 85-105.

Stephan, I. (2008). ‘Kunstepoche’. In Deutsche Literaturgeschichte. Von den Anfängen bis zur Gegenwart (pp. 182-238). Stuttgart: J.B. Metzler.

Todorov, T. (1981). Introduction to Poetics . Brighton: The Harvester Press Ltd.

Toolan, M. J. (1988). Narrative: A critical Linguistic Introduction. London : Routledge.

Turchin, B. (1987). The Nineteenth-Century Wanderlieder Cycle. The Journal of Musicology, 5(4), 498-525.

Images

Die Frankfurter Nationalversammlung im Mai 1848. Zeitgenössischer Holzschnitt, koloriert. (picture alliance / Bianchetti / Leemage)

Porträt von Friedrich von Schiller von 1780. Fotograf: Roger Viollet/Getty Images

https://www.theguardian.com/stage/2009/nov/22/friedrich-schiller-anniversary-film-biography

Caspar David Friedrich 1818, Ölgemälde, Hamburger Kunsthalle

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wanderer_above_the_Sea_of_Fog

Otto Nowak / CCI / Bridgeman Images

https://www.newstatesman.com/culture/music/2022/02/the-enduring-chill-of-schuberts-winterreise

Die Winterreise, Caspar David Friedrich ca. 1827

www.desingel.be/dadetail.orb?da_id=18598

Winterlandschaft, Caspar David Friedrich 1811

https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/winter-landscape/3AFa-YVB1DBOwA?hl=en-GB

Ansicht von Lübeck, Andreas Aschenbach

https://www.meisterdrucke.com/kunstdrucke/Andreas-Achenbach/299857/Ansicht-von-Lübeck,-1869.html

Steglitzer Gruppe um 1930