Watercolour by Denis Dighton, 1815

Watercolour by Denis Dighton, 1815

Socio-political background

The Thirty Years’ War left the German-speaking principalities under the influence and control of France, which promoted the sovereignty of the German princes and their establishment of autocratic regimes (Reinhardt, 1950). The ideas of princely absolutism, which built on the concept of inequality formulated by Aristotle several hundred years earlier, found expression in the writings of Niccolo Machiavelli (1469-1527) and were also adopted by the French Emperor Louis XIV (1638-1527) who wrote in his instructions to the Dauphin:

“We are the representatives of God. Nobody has the right to criticize our actions. Whoever is born a subject must obey without asking.“

Louis XIV 1715 (Longnon, 2001)

According to Simms, both rural and urban communities within the 18th-century German principalities were under a hierarchical structure in which domination and obligation played a key role. He describes the 150 years from the Thirty Years’ War to the French Revolution as a continuous struggle for dominance in Europe, fueled by the imperial efforts of those in power. Simms refers to a quote from the contemporary German philosopher Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, who described Germany as the battlefield on which the struggle for European supremacy took place. He explains that Germany at the end of the 18th century consisted of a loose collection of independent, semi-independent and dependent territories that made up the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation (Simms, 1998). During the 17th and 18th centuries, the philosophies of the Enlightenment continued to spread in Europe, sparking criticism of absolutist state governments and their oppressive regimes. This critical attitude and the increasing social injustices contributed to the outbreak of the French Revolution in 1789. Simms explains how a more equal and unified French society was created under the banner of liberty, equality and fraternity. In the process, all feudal privileges were abolished and replaced by a social order based on merit rather than birth, church property was nationalized while the church itself was placed under the government, and pressure was placed on the kingdom’s many national and linguistic minorities to adopt the French language and culture. Since this new social structure challenged the feudalistic societies of neighboring Western and Central European countries, the impression arose that the ‘new regime’ would only have a chance of survival if the revolution was spread across Europe. To achieve this was initially the ideological intention of the revolutionary wars. The Holy Roman Empire was seen as an enemy because it represented everything that the ‘new regime’ despised: a reactionary jumble of small ecclesiastical areas and principalities (Simms, 2014). The philosopher and political activist Thomas Paine, who was instrumental in both the American Wars of Liberation and the French Revolution, wrote in a letter to the Marquis de la Fayette in 1792

“I hope it ends in a war against German despotism and in the liberation of all of Germany. If France will be surrounded by revolutions, she will be in peace and security.”

A French revolutionary wrote in the same year

“The Holy (Roman) Empire, this monstrous assembly of despots great and small, must also disappear under the impact of our incredible revolution. The Kingdom of France supported it, the French Republic will work for its destruction.”

Since the revolutionaries felt that they were surrounded on all sides by hostile powers, they called on French society to rise to the challenge, founded revolutionary armies and introduced universal conscription in 1793. Napoleon Bonaparte, the most victorious general in the revolutionary armies, became so politically powerful that he was crowned French Emperor in 1804 with the crown of Charlemagne. According to Simms, Napoleon primarily wanted to dominate Europe and unite it on French terms and for France’s benefit. The execution of this plan required him to control Germany in order to secure its resources and use the legacy of the Holy Roman Empire for his own imperial purposes (Simms, 2014). Reinhardt points out that the Napoleonic invasion of Germany was inspired by the same imperial motives that initiated the Thirty Years’ War between 1618 and 1648. Napoleon himself declared: “I will play the role that Richelieu assigned to France” (Bonaparte in Reinhardt 1950: 323). In doing so, he continued the imperialist efforts of Louis XIV. Napoleon eventually achieved his goal and defeated both the Prussian and Austrian armies, leading to the inglorious end of the Holy Roman Empire (Reinhardt, 1950). The experience of loss of territory, loss of sovereignty and disarmament that was the result of the Thirty Years’ War was repeated with Napoleon’s triumphant entry into Berlin and the following years, which were marked by occupation and demands for war reparations. According to Simms, this experience of invasion, division and occupation by France traumatized an entire generation of Germans (Simms, 1998).

Mezzotint by Jazet after Steuben, published by Jazet and Theodore, Vibert, Bance and Schroth, 1870.

Mezzotint by Jazet after Steuben, published by Jazet and Theodore, Vibert, Bance and Schroth, 1870.

Socio-cultural background

The historian Karen Hagemann describes how Napoleon’s victory over the Prussian army in 1806 led to a social, political and economic crisis in Prussia, affecting large parts of the population and sparking an intense public debate in patriotic circles about the origins of the defeat (Hagemann , 1997) (Hagemann, 2006). The betrayal of the German princes who had joined Napoleon, along with a lack of national attitude, was blamed for the defeat. It also became clear that the Prussian state and its military were in need of fundamental reform and that French-style universal conscription was necessary to counter French oppression. Hagemann describes how the awakening of a nationalist spirit and the construction of a German national myth became a necessity in an attempt to build a ‘patriotic willingness to sacrifice’. According to Hagemann, the willingness to take up arms was further strengthened by the middle class’s hope for political emancipation. While the French occupation lasted until 1808, the Prussian king entered into an alliance with Napoleon before the Grand Army’s invasion of Russia in 1812 and made Prussia a deployment area for the invading troops, further increasing economic hardship.

When Napoleon was defeated in Russia in December 1812, censorship of nationalist propaganda was lifted, and patriotic sentiments were spread across a variety of media to mobilize the population for the coming war. According to Hagemann, the role of songs was particularly important in this context, as songs could reach even less educated sections of society. She emphasizes the tradition of the military song, which was already used as a propaganda medium during the French Revolution. Hagemann makes clear that the most important function of patriotic songs and poems appeared to be to provide historical and religious legitimacy for the armed struggle and to provide emotionally charged images and stereotypes that promoted a collective self-perception. The image of the nation as a ‘national family’ and the army as a ‘community of brothers’ falls under this category. Religious and popular language enabled patriotic songs and poems to appeal to all classes by drawing on common knowledge and accepted norms. According to Hagemann, patriotic propaganda literature also promoted the concept of the German national character, which was constructed as a counter-image to the hostile French neighbor: virtuous, sensitive, profound, loyal, upright and brave (Hagemann, 1997). In contrast to patriotic songs that portrayed armed combat as a joyful task, there were also anti-patriotic and pacifist songs that showed that enthusiasm for war and the ‘Fatherland’ was not evenly distributed among the population.

It was not only language-based media that played an important role in promoting patriotic feelings, but also painting, sculpture and architecture, which were used to promote a sense of collective identity through the construction of a national historical and mythological past.

Bildtapete Olympische Feste 1824

Bildtapete Olympische Feste 1824

The cultural historian Robin Lenman describes how, after the end of the Napoleonic Wars (1815), a market for contemporary art began to develop with picture lotteries and traveling exhibitions organized by art unions, leading to the establishment and growth of art academies and national galleries and to the production, exhibition and the sale of paintings. It was also an effort to overcome what was perceived as Germany’s cultural deficit, towards other European nations and its failure to ‘challenge the artistic hegemony of France’.

Lenman highlights that international exhibitions of contemporary art became ‘masculinity contests’ between European countries similarly affected by the Napoleonic Wars and now also using art as a propaganda medium.

Lenman highlights that international exhibitions of contemporary art became ‘masculinity contests’ between European countries similarly affected by the Napoleonic Wars and now also using art as a propaganda medium.

Interest in history as an academic discipline, which had begun before the 18th century, was also suddenly stimulated by the Napoleonic occupation, fueled by the urge to focus on distant and more glorious times in order to evoke patriotic feelings and to convey a sense of collective identity. Lenman describes how historical societies and museums were founded and how history became an important part of intellectual debates, had a significant influence on architecture, became a theme in literature, and in painting, now ranking third after biblical and mythological themes. Investment in public art in the form of frescoes, sculptures and monuments was intended to further help establish a relationship with history, with inaugurations and speeches providing additional opportunities for patriotic propaganda.

Lenman emphasizes that it was the men of the educated German middle class who, although they represented a minority at the time, were the protagonists of this propaganda and increasingly saw themselves as ambassadors of German culture, which was considered a source of national values. He points to the unequal participation of social groups in this process, with the working class excluded from the enjoyment of the arts and invisible to artists, even though the latter saw themselves as representatives of the entire nation (Lenman, 1997).

The historical sociologists Eric Hobsbawm and Benedict Anderson also share an understanding of nationalism as an intellectual construction, a perception that informed the studies of both Hagemann and Lenman. Hobsbawm views national traditions as well as beliefs and value systems as inventions intended to convey values and norms of behavior, and he views symbolically and emotionally charged signs as created to evoke a sense of group membership. Hobsbawm sees the crucial importance of history as being a reminder of belonging to a lasting political community. Elites are seen as the protagonists of this recent nation-building (Hobsbawm, 1983). Anderson views nations as imagined political communities conceived as deep horizontal fellowships and traces the concept to the great religious imagined communities of the Middle Ages, seeing the nation as a modern secular equivalent (Anderson, 1983).

Cultural production sample the war song

Cultural production sample the war song

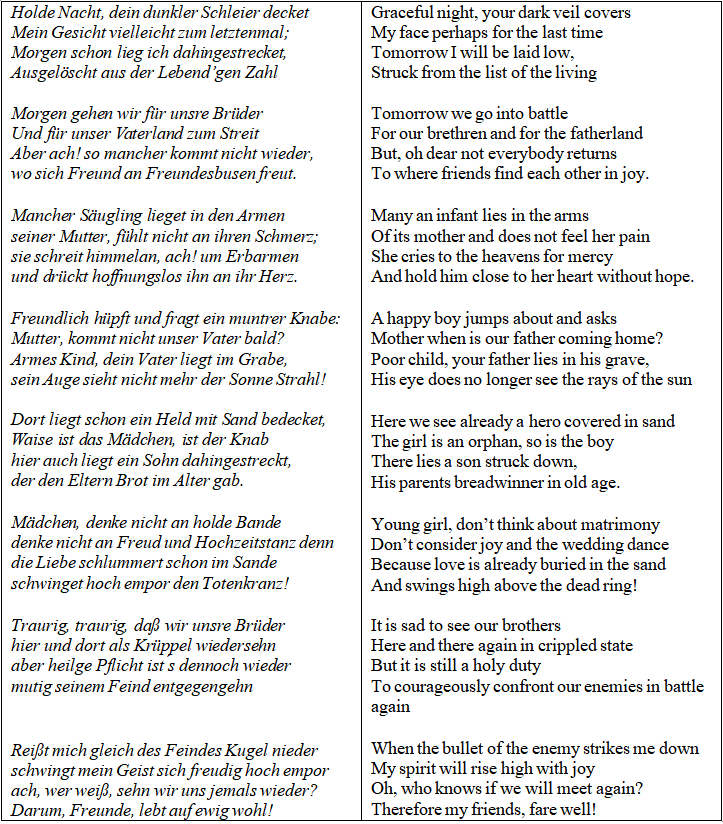

,Holde Nacht, dein dunkler Schleier decket‘

Chapter 2 – The German Context

Interpretation of the song lyrics

Interpretation of the song lyrics

The feeling of an imaginary community is expressed in the song ‘Holde Nacht …’ in the first two lines of the second verse ‘Tomorrow we go to fight for our brothers and for our fatherland’. It was this feeling of belonging to and defending a group that was meant to mobilise the listeners to be willing to sacrifice their lives.

The human experience of change over time is described by the philosopher Paul Ricoeur as the characteristic element of narrative texts (Ricoeur, 1984). Although the lyrics of the song ‘Holde Nacht…’ are limited in their narrative content, they also represent a change in time that is triggered by the war. Describing life in peacetime and contrasting it with life shattered by war, the song expresses in eight verses the anticipation of loss and grief that the experience of war holds in prospect.

There are multiple subjects in the narrative of the song’s lyrics: the individuals and the groups affected by the war. The respective subject changes in each stanza, starting with the individual soldier in the first, which is made clear by the use of the first person singular ‘Tomorrow already I lie stretched out…’. In the second stanza the perspective is extended to the soldiers as a group, which is expressed through the use of the first person plural ‘Tomorrow we go for our brothers…’. In the following four stanzas the ‘subject’ switches to the infant and his mother, the boy and his mother, a boy and a girl who become orphans, parents who lose their son and a young girl who loses her prospect of marriage. The third person singular is used in those four stanzas. Stanza five returns to the group of soldiers, expressed by the first person plural ‘Sad, sad, that we have lost our brothers…’ and stanza six to the individual soldier in the first half of the stanza, and finally to the group of soldiers, expressed in the last half of the stanza by the first person singular or plural respectively. The song reflects the situation on the eve of battle, in which the prospect of death, injury and loss is expressed from the perspective of those affected by the war. The view of those who directly experience the war, here the soldiers individually and as a group, frames the view of those who are indirectly affected by it, friends and relatives at home.

The French literary theorist Gerard Genette defines three aspects of narrative time: order, duration and frequency (Genette, 1980). Applied to the lyrics of the song we find the use of the adverbs ‘tomorrow’, ‘morning already’, ‘already’, ‘immediately’, and ‘soon’ in six of the eight stanzas. This makes it clear how much the feeling of expectation is present in the verses of the song. A reference to duration appears in the first stanza: ‘for the last time’ and in the last stanza ‘ever’ and ‘forever’. The use of superlatives here creates emotional intensity and gives the situation drama and the impression of finality. The last line is a farewell call and reinforces this impression. We only find the frequency in the sense of repetition in verse seven, in which the soldier’s duty to face the enemy ‘again’ is mentioned.

These last two lines of the seventh verse and the following two lines of the eighth verse contrast with the main body of the song, which can be seen as a lament and expression of the experience of loss and fear of loss from a variety of perspectives. While the last two lines of the seventh stanza express a patriotic perspective in which it is a ‘sacred duty’ to face the enemy in battle, in the next two lines death in battle is presented as a heroic act. This means that what looks like a defeat from the outside becomes a victory from this perspective. The contrast between being shot down by the enemy’s bullet ‘Tears me down like the enemy’s bullet’ and the joyful ascension of the spirit ‘my spirit soars joyfully high’ further expresses this paradox. All four lines reflect the political propaganda of the time, in which participation in the war was presented as a heroic and worthy obligation. Interestingly, it is precisely in these lines that a strong connection to religion and spirituality is established. The duty of going into battle is a ‘sacred’ duty, and after the soldier is struck down, it is his ‘spirit’ that rises with joy.

No such reference to spirituality or religion is made in the other parts of the song. The enemy is only named in these lines. In all other verses, it seems to be the war itself that destroys lives and causes loss and pain on many levels. The only other patriotic element in the song is found at the beginning of the second verse, where ‘going to war’ is portrayed as a virtuous altruistic act ‘Tomorrow we go to fight for our brothers and for our fatherland’. The second stanza is therefore connected to the lines of the seventh and eighth stanzas and their propagandistic orientation. It is these lines that probably made it possible for this song to be approved as an official war song. In all other parts of the song, the lyrics become emotionally charged due to the song’s focus on human relationships: the bond between friends, the relationship between child and mother, between a child and his parents, a son and his aging parents, a young girl and her lover. The plaintive element is reinforced by the use of contrasts where positive emotions are nullified by the destructive experiences of war: the boy jumping around happily asking when his father will return while the father is long buried; the girl who receives a funeral wreath instead of a wedding dance; the young mother who holds her baby hopelessly close to her heart. Romantic metaphors that refer to nature, such as the fair night that covers the soldier’s face with a dark veil, the eye that no longer sees the sun’s rays, the hero that is already covered with sand, the mother that cries out to heaven for mercy, further contribute to the emotional character of the song and reinforce the impression of tragedy.

That fear, sadness and pain are prominent among these emotions is clearly demonstrated by the repetition of the adjective ‘sad’ at the beginning of stanza seven, the use of the adjective ‘poor’, the noun ‘pain’ and the verbs ‘scream’ and ‘cry’ ‘. According to Toolan (1988), both adjectives and actions can provide clues to characterization and help distinguish between perpetrator and victim. Since the adjective and action mentioned above are used in connection with the subjects of the song – the ‘poor child’, ‘the mother… in her pain… cries out to heaven’, the subjects are thereby defined as victims which is confirmed by the repeated use of the verb ‘stretched out’ and the verb ‘erased’ (both in passive mode). War itself can be defined as a ‘perpetrator’ in this context through its destructive effects. The overall tone of the text, written from the perspective of the victims, is therefore one of fear and dark foreboding, despite its optimistic patriotic insertions.

Conclusion

While the song ‘Holde Nacht…’ reflects the experience of war by those directly and indirectly affected through its effects. It expresses the feelings of fear, pain and loss, but it also contains the patriotic elements characteristic for war songs of the time. However, these patriotic lines contrast with the overall tone of the lyrics and seem more obligatory than personally motivated. Here it becomes clear that the patriotic perspective was a view imposed from outside and not a way of seeing that emerged from personal experience. The history of the song is also interesting. The German linguist and folklorist Wolfgang Steinitz assumes that the song ‘Holde Nacht..’, whose author is unknown, was written by a member of the Prussian military and dates from the war years 1813-15. According to Steinitz, it made such a deep impression on the soldiers and made them so wistful that it was banned in some of the troops. The song ‘Holde Nacht..’ was widely distributed through pamphlets since the beginning of the wars of liberation (Steinitz, 1979).

A contemporary reports:

“In 1813 I often heard the soldiers and later the young people singing; The song always had a moving effect on me, the boy. As with me, so with others.”

Kantor Jacob aus Konradsdorf bei Haynau, Schlesien, 1840

The important role that interpersonal relationships play, as discussed in Chapter 1, is evident in the song ‘Holde Nacht..’. It was the anticipation of the loss of these relationships that touched the soldiers so deeply before the battle, making them think not only of themselves and their own impending death, but of all those who would be affected. Patriotic propaganda also took advantage of the importance of emotional interpersonal relationships and used terms that suggested a close connection (fatherland, brotherhood, etc.) to motivate soldiers to fight. The idea of social community was already fundamental to the French Revolution with its call for freedom, equality and fraternity. However, the call for equality was used to introduce universal conscription, which resulted in revolutionary armies becoming large enough to fulfill imperialist ambitions. Thus, the desire for equality, which questioned the concept of inequality on which imperialism was based, was turned into its opposite and the need for social cohesion (fraternity) was exploited in order to win the population over to imperialist military campaigns.

The Prussian wars of liberation were a reaction to Napoleon’s imperialist invasion and a similar patriotic nationalist discourse became necessary to convince the population of the German principalities of the need for participation in military service and to mobilize them for the wars of liberation. Hageman describes how the idea of nationalism promoted by the German middle class at this time was based on concepts that had developed since the mid-18th century. According to Hageman the idea of the nation was in this context, a cultural construction, created by the men of the German educated middle classes. The patriotic national discourse, the forms of representation of the nation and the practice of the national movement were therefore shaped by their fears, wishes, needs, hopes and visions. In this context, Hageman emphasizes that these men were more affected than any other social group by the economic, social, political and cultural changes caused by war and revolution and experienced mental disorientation and socio-cultural insecurity that also affected their self-image and masculinity (Hagemann, 1997).

The fact that there is a connection between a problematic gender identity and violence was already mentioned in Chapter 1, with reference to the concept of ‘hypergender’ developed by Scheff. The characterization of the German man as brave and defensive and of the German woman as domestic and religious, promoted by German patriotic writings, comes close to what Scheff describes as hypermasculine and hyperfeminine types. According to Scheff, these types arise when experiences of either shame, loss or humiliation are not processed. The feeling of loss of social connection that arises from these experiences on a personal level can be compared to the feeling of loss of social connection that the men of the German educated middle classes experienced since the end of the 18th century. Hagemann points out that the national myths, symbols and rituals, as well as the ideal of male defensiveness, which were created back then to mobilize the population for the wars of liberation, have remained relevant to this day (Hagemann, 1997).

Quotes from contemporaries confirm that the French wars, sieges and the collapse of the empire were experienced by many as humiliation. The geographer August Zeune bitterly noted in 1808 that the Germans “were treated like animals, exchanged, given away, (and) trampled on… like a ball… passed from one hand to the other” (Simms, 2014). In a brochure published in 1806 by the Nuremberg bookseller Johann Philipp Palm entitled “Germany in its deepest humiliation” it says

“Without emotion, a German cannot even look at the humiliation of his fatherland, much less feel it personally and speak about it publicly.”

(unknown, 1877)

Scheff emphasizes that experiences of shame and humiliation, if not acknowledged and processed, have the potential to lead to violent actions. The fact that an acknowledgment of the experience of humiliation at that time was not possible was made clear by the fact that Philipp Palm was in the same year convicted to death by Napoleon and poublicly executed for publishing the brochure ‘Germany in its Deepest Humiliation’.

The execution of Johann Philipp Palm

The execution of Johann Philipp Palm

Bibliography

Anderson, B. (1983). Imagined Communities: Reflections On the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso.

Genette, G. (1980). Narrative Discourse: an Essay in Method. New York: Cornell UP.

Hagemann, K. (1997). Of “Manly Valor” and “German Honor”: Nation, War and Masculinity in the Age of the Prussian Uprising against Napoleon. Central Europeen History, 30(20), 187-220.

Hagemann, K. (2006). Occupation, Mobilization, and Politics: The Anti-Napoleonic Wars in Prussian experience. Central European History, 39(4), 580-610.

Hobsbawm, E. (1983). The Invention of Tradition. Cambridge: Cambridge UP.

Lenman, R. (1997). Artists and Society in Germany 1850-1914. Manchester: Manchester UP.

Longnon, J. (2001). Mémoires de Louis XIV. Jean Longnon, Tallandier, Paris 2001. Paris: Tallandier.

Reinhardt, K. F. (1950). Germany: 2000 Years. California: The Bruce Publishing Company.

Simms, B. (1998). The struggle for Mastery in Germany 1779-1850. London: Macmillan Press.

Images

Watercolour by Denis Dighton, 1815

https://collection.nam.ac.uk/detail.php?acc=1975-05-7-1

Mezzotint by Jazet after Steuben, published by Jazet and Theodore, Vibert, Bance and Schroth, 1870 (c)

https://collection.nam.ac.uk/detail.php?acc=1971-02-33-437-1

Bildtapete “Olympische Feste” im Herrenhaus Rüdigsdorf (Sachsen) von 1824

https://www.monumente-online.de/de/ausgaben/2007/2/liebestolle-goettinnen-blumen-und-girlanden.php

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bronzestandbild_-_panoramio.jpg

https://www.versobooks.com/en-gb/blogs/news/4011-imagined-communities-an-introduction

https://deutsche-schutzgebiete.de/wordpress/befreiungskriege-1813-1815/

https://de.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Datei:Hinrichtung_Johann_Philipp_Palms.jpg